As a childhood asthmatic, Wesley Moore’s early exposure to the medical world saw physicians become his role models. By adolescence he was committed to forging a path in the profession. After choosing a surgical path, rapid advancements in the field of vascular surgery peaked Moore’s interest and resulted in an illustrious career spanning several decades. Moore spoke to Vascular News about his journey so far, his ongoing research in the form of the CREST trials and what he thinks the future holds for vascular medicine.

Why did you decide you wanted a career in medicine, and why in particular did you choose to enter the vascular field?

I was a childhood asthmatic in an era when there was limited medical treatment. I was therefore exposed at an early age to physicians who I respected and they became my role models. As a result, by the time I was in high school, I decided that medicine was the profession for me. When I first started medical school, my plan was to specialise in internal medicine. However, by the time I was in my final year, it was clear that I wanted to be a surgeon. When I started my general surgery residency, my service chief and programme director had just returned from Houston where he did a vascular fellowship. His primary interest in our programme was vascular surgery. Our programme was rich in patients with vascular disease. Vascular surgery in the 1960s was in rapid development and was the exciting area during my training. Therefore it was no surprise that I was attracted to that specialty. I managed to get as many rotations as I could on vascular services during my general surgery residency. Upon completion of my general surgery residency, I had a two-year obligation to serve in the US Army in Germany. Upon completion, I did a one-year vascular surgery fellowship at the VA Hospital/UCSF in San Francisco.

Who have been your most important career mentors and what wisdom did they impart?

There were three surgeons who had a major impact on me and my subsequent career. The first was H Glen Bell. Dr. Bell was the first general surgery programme director at the University of California, San Francisco. By the time I was a medical student at that institution, Dr. Bell was Professor Emeritus, but he still had a busy surgical practice. Dr. Bell taught me several values. He was predictable in that you always knew what he expected including what time to be on the floor for rounds. He had an excellent patient rapport. Finally, no case was too small for him to give his undivided attention. The second was F William Blaisdell. Dr. Blaisdell was chief of Surgery at the San Francisco VA and my programme director when I began my residency at the University of California, San Francisco sponsored programme at the VA. Dr. Blaisdell had just completed a vascular fellowship at Baylor in Houston with Drs DeBakey, Cooley, and Crawford. He taught me many things including devotion to patient care, technical excellence, a love for academic productivity, and just plain hard work. The third mentor was Albert D Hall. Dr. Hall was the assistant chief of Surgery during my residency and became chief of Surgery during my vascular fellowship. Dr. Hall never did an operation before reading every paper he could find on the subject. He was always the best-prepared surgeon in the operating room. We all tried to follow his example, but I am afraid that most of us fell short. He taught me the importance of strict attention to detail as well as technical excellence. I am indebted to Dr. Hall for many things including my first academic appointment at UC San Francisco and chief of vascular surgery at the VA Hospital upon completion of my vascular fellowship.

What has been the biggest development(s) in vascular medicine during the course of your career?

My career has spanned from 1960 to the present, in which time the golden age of achievement in the management of patients with vascular disease has occurred. The development of prosthetic vascular grafts, synthetic sutures, new operations including extra-anatomic bypass, the vascular diagnostic laboratory with non-invasive testing including duplex ultrasound, and finally endovascular surgery with less invasive methods for treating a variety of condition and, in particular, aortic aneurysm.

What are some of the proudest moments in your career?

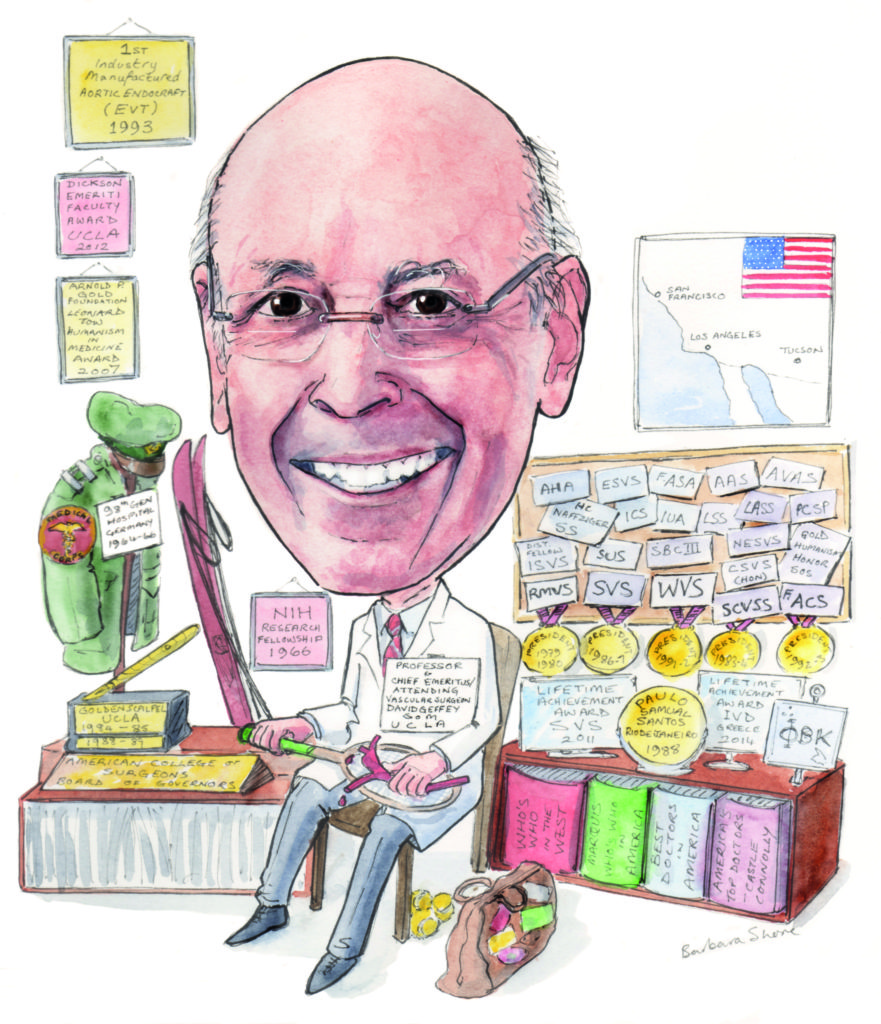

Assisting Dr. Blaisdell in performing the first axillo-femoral bypass, election to membership in the Society for Vascular Surgery, starting a vascular surgery programme at the University of Arizona, succeeding Wiley Barker as professor and chief of Vascular Surgery at UCLA, performing the first industry manufactured aortic endograft (EVT) in 1993 worldwide, starting the Western Vascular Society, election as secretary and subsequently president of the Society for Vascular Surgery, and finally receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for Vascular Surgery.

What new vascular technology are you watching closely and why?

One is direct carotid stent/angioplasty with flow reversal (TCAR). All of the prospective randomised trials comparing carotid artery stenting (CAS) via the transfemoral approach with distal embolic protection to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) have shown that periprocedural stroke/death rates are twice as high with CAS compared to CEA. However, once past the periprocedural risk, the event curves of CEA and CAS become parallel, suggesting that the long-term durability and protection from stroke are comparable for both CEA and CAS. The issue is how to reduce the increased periprocedural risk with CAS. Part of the increased periprocedural risk with transfemoral CAS may be related to the need to traverse a diseased aortic arch and the need to traverse the carotid lesion in order to place a distal protection device. The direct carotid approach avoids the aortic arch and flow reversal for embolic protection avoids the need to traverse the lesion. The results of the recently published ROADSTER trial have shown a very low complication rate in high-risk patients, comparable to the best results reported with CEA.

Based on the results of the CREST trial, when would you recommend stenting over endarterectomy, given the higher risk of associated stroke?

I have not and will not recommend CAS using the transfemoral approach.

Based on data from CREST you have shown that some plaque characteristics can predict intervention risk. Can you please explain these findings?

We recently analysed the CREST data with respect to lesion characteristics in order to determine if there were specific lesions characteristics that carried a high complication rate with CAS but not CEA. We found that long lesions in excess of the median length of 12.8mm, tandem lesions, and lesions distal to the carotid bulb carried a high risk for CAS, but not CEA. Absent of these lesion characteristics, CAS and CEA had equal results. However, only one-third of the patients in CREST, in retrospect, would have been considered safe for CAS.

What is the current status of the CREST-2 trial? How do you hope this will build on the findings of the CREST trial?

To date, we have randomised 200 patients in CREST-2. This study is critical for the future treatment of asymptomatic patients with carotid artery disease. There are observational data to suggest that intensive medical management including the use of statins has materially reduced stroke risk in patients with asymptomatic, haemodynamically significant carotid stenosis. This has led many countries, not including the USA, to limit intervention to symptomatic patients only. In the USA, more than 90% of carotid interventions, primarily CEA, are done on asymptomatic patients. If CREST-2 shows no benefit of CEA or CAS compared with intensive medical management, this will have a profound effect upon our practice. On the other hand, if either CEA or CAS or both show significant benefit over intensive medical management alone, it will validate our current practice and have an international impact.

Could you tell us about one of your most memorable cases? What did this experience teach you?

One of my most memorable cases, and one of historical interest, occurred when I was an assistant resident in 1962. I was helping my chief resident resect an abdominal aortic aneurysm on a patient with an above-knee amputation. In those days we routinely carried out the repair with a bifurcated graft. We had completed the proximal anastomosis and the distal anastomosis on the side of the patient’s intact leg. When we went to do the distal anastomosis on the side of the amputation, we discovered that the iliac artery was chronically occluded. We solved that problem (or so we thought) by cutting off the other graft limb and oversewing the stump. The patient was transferred to the ICU where he was doing well until 24 hours later, his graft occluded, rendering him ischaemic from the umbilicus distally. We returned the patient, emergently, to the operating room to carry out a revision. However, with the induction of anesthesia, the patient had a cardiac arrest. The concept of closed-chest resuscitation had just been published. We successfully carried out closed-chest compression and got the patient’s heart started.

We were now faced with a patient who had just had a cardiac arrest in whom the lower half of his body was ischaemic. At this point, we decided we needed some senior help and called Dr Blaisdell. Dr Blaisdell thought about the situation for about 15 minutes and came up with the idea of the axillo-femoral bypass. With the patient awake, but intubated, we exposed the right axillary and right femoral arteries under local anaesthesia. At that time, no tunnelling instruments existed, so we improvised using an external vein stripper (the longest instrument we had) and with the use of a small counter incision midway, we created a tunnel and passed a 10mm Dacron graft between the two incisions and completed end-to-sides anastomoses. This successfully restored circulation. That patient recovered and lived for another five years.

There are many lessons to be learned from this case. Here are a few:

- Make sure you check out all of the arterial anatomy/pathology before beginning the reconstruction. Had we done that we would have realised that the left iliac was chronically occluded and would have used a tube graft;

- Do not be constrained by tradition or routines. Even though it was routine to use a bifurcated graft at that time, be flexible in your thinking and be prepared to do something different such as preferentially using a tube graft as we do today;

- Be prepared to be inventive when faced with a new situation;

- Do not be afraid to ask for help when you are in trouble.

What advice would you give to young vascular surgeons starting out in their careers?

Be selective and conservative in choosing your first cases. Make sure that there is a high likelihood that there will be a good outcome. Recognise that change is inevitable; what you learned in your training is likely to become obsolete during your professional life. While being cautious, be prepared to adopt new approaches to managing problems.

What three questions in vascular medicine still need to be answered?

There are too many to pick out the top three! I would include:

- What is the best way to approach patients with combined carotid/coronary disease?

- Are there pharmacologic means to prevent or remove atherosclerotic plaque?

- What is the best way to prevent failure due to myointimal hyperplasia?

What are some of your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I still love tennis, skiing, and travel.

Is there anything else that you would like to mention that we have not yet covered?

I have been very fortunate in my career, but it would have never happened without a very supporting wife, family, and mentors.

Fact File

Education

- 1955 BS, University of Southern California, USA

- 1959 MD, University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco, USA

Current position

- 2004–present Professor and chief emeritus/attending vascular surgeon, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, USA

Previous appointments (selected)

- 1960–63 Assistant resident in General Surgery, University of California Hospitals, San Francisco

- 1963–64 Chief resident in General Surgery, University of California Hospitals, San Francisco

- 1964–66 Captain, Medical Corps, 98th General Hospital, Germany

- 1966–77 Chief, Vascular Surgery Section, VA Hospital, San Francisco

- 1968–73 Assistant professor of Surgery, University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco

- 1973–77 Associate professor of Surgery, University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco

- 1975–77 Assistant chief of Surgery Service, VA Hospital, San Francisco

- 1977–80 Professor of Surgery, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson

- 1977–80 Chief, Vascular Surgery Section, Arizona Health Sciences, Tuscon

- 1980–84 Staff surgeon, Wadsworth VA Hospital Los Angeles

- 1984–93 Staff surgeon, Sepulveda VA Hospital, Sepulveda

- 1980–96 Chief, Vascular Surgery Section, UCLA Center for the Health Sciences, Los Angeles

- 1980–96 Program director, General Vascular Surgery Residency, UCLA Center for the Health Sciences, Los Angeles

- 1980–2004 Professor of Surgery, University of California David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles