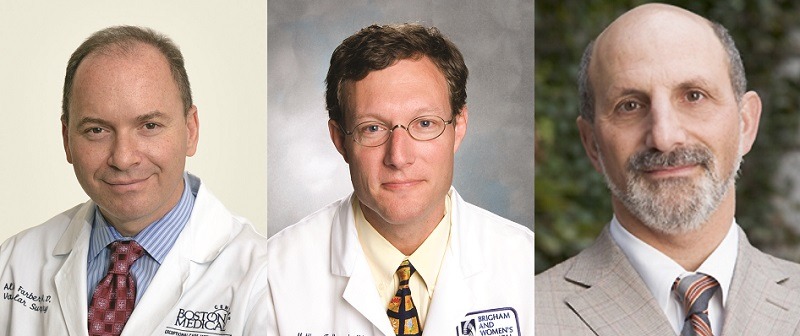

Vascular News spoke to the principal investigators of the BEST-CLI (Best endovascular versus best surgical therapy in critical limb ischaemia) trial—Alik Farber (Boston Medical Center, Boston, USA), Matthew Menard (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA), and Kenneth Rosenfield (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA)—about its current status, the challenges of conducting follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the “remarkable” support they have received from societies and industry.

The BEST-CLI trial, which completed enrolment in December 2019, is a prospective, randomised, multicentre study which aims to compare the efficacy, functional outcomes, and cost of endovascular therapy versus open surgical bypass in patients with chronic limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI) and infrainguinal peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Menard detailed that the trial consists of “two trials in one,” with the larger of the two involving the randomisation of endovascular therapy against open surgery “in the situation in which it was favourable for open surgery, in the sense that the patient had a single segment of greater saphenous vein,” as it has been established that this “is associated with the most favourable outcomes for open surgery.”

Commenting on the rationale behind including a second, smaller component, he explained: “We did not think it was fair to just test the best case of open surgery against all-comers of endovascular therapy and so we included a second cohort as well in which patients that did not have that good single segment of saphenous vein, either in the affected leg or in the other leg, would also be investigated.”

Enrolment and follow-up has been completed in the smaller cohort, “the so-called ‘disadvantaged conduit’ cohort,” and follow-up is currently ongoing for the larger group.

“The most impactful trial of the decade in PAD”

In terms of follow-up, Farber commented that the investigators hope to reach the two-year mark, so as to attain “enough power to answer the important questions that we are asking”, such as “what is the best treatment for patients with CLTI, who are candidates for both endovascular therapy and open vascular surgery?”

On the topic of importance, Rosenfield stressed the belief of the research team that this is “the most impactful trial of the decade in PAD, and of course the focus is on CLTI, which is the most severe form of PAD.”

He continued: “We think the trial is incredibly important and I think the vascular community also believes it is asking the most relevant questions there are to be asked right now.”

Rosenfield also addressed the fact that enrolment has not been easy, despite the importance of the questions they are asking: “There are lots of evidence gaps throughout the vascular space, but this is an important one because of the preconceived notions and biases. I think with this trial it has been more challenging to get going, to enrol, and to get people on board to believe in equipoise and being willing to actually randomise patients than any of us may have anticipated.”

“A tremendous challenge”: Conducting research during COVID-19

One of the big challenges the BEST-CLI trial has faced in recent times is the COVID-19 pandemic. Farber detailed that Massachusetts has been “horribly affected” and that “everything has been shut down”. Research activities have been suspended and therefore elective patient visits have been cut down to a minimum. In response to this, the team is using telehealth in order to collect data, but this has come with its own challenges.

“It is hit and miss,” said Farber of telemedicine. “For the patients that can use the necessary apps, it works, but for some of our patients who are more debilitated, for those who are less savvy with computers, telephone calls are easier. Certainly it is not as good as seeing patients in person, but it is a reasonable substitute.”

Menard pointed out that the COVID-19 crisis has created “a tremendous challenge” for the entire research community, but that CLTI poses a particular difficulty: “CLTI is a disease that affects the foot and one of the hallmarks of it is ulcers of the feet, which is obviously challenging to assess remotely.”

He also detailed that the team have had to grapple with the conundrum of whether to collect “whatever data we can” during this period of uncertainty or just to “pause completely and resume at a later date”. They decided that the best course of action was to collect data where possible, but that there is no hiding from the fact that this is a “phase of suboptimal data collection”.

Rosenfield stressed that the research team is addressing the pandemic in “a very proactive way,” adding that they “fully intend to capture all of the information we possibly can and is necessary to complete this trial. It may require some workarounds but that has become the norm for all of us now, whether it is through virtual communication or a slight delay to a visit. Either way we intend to accrue that information and we are actually starting now to finally have the opportunity to put the data together.”

Menard also stressed that the CLTI population is one that is “particularly vulnerable in general and at baseline” and so the investigators are “very interested” in learning exactly what the prevalence of COVID-19 is in the BEST-CLI patient population and in CLTI patients in general.

“It certainly seems that they are high risk but we do not know exactly how it is playing out yet,” he commented.

Overcoming a “financial hurdle”

Aside from the acute challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the BEST-CLI trial has had to deal with a number of obstacles not uncommon to investigator-initiated studies.

Menard explained that, during enrolment, the investigators encountered “a financial hurdle,” detailing that their National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsor had “a strong willingness” to help them complete the trial, but ultimately was unable to provide any additional funding. “We were forced into a situation in which we had to decide how best to proceed.”

“We reached out to all our societal partners, we reached out to industry partners, and other relevant stakeholders, and I am happy to report that we have been able to raise over US$3 million to extend our follow-up,” Menard revealed.

“I think all of us believe that that success is an absolute reflection of the desire of the vascular community to see the BEST-CLI trial succeed and finish in a way that maximises its potential. This effort continues, but we are extremely grateful to all those that have supported the trial in this moment and it is going to translate into the desired success.”

Farber concurred: “It has been remarkable to see the vascular community as a whole, from societies to industry to not-for-profit organisations like VIVA [Vascular Interventional Advances], to step up in a big way and recognise the importance of sticking together as a community.”

“It has been really heart-warming to us and a validation of the trial and its mission, which is to improve the outcomes for patients and also to improve the cost of care and quality of life—those are two very important components of this trial which I think cannot be overstated in terms of their importance.”

Next steps: “A treasure trove of Level 1 evidence”

“We are excited,” expressed Rosenfield, considering the next stage of the trial. “We are on the descending curve of the hard part of this trial and about to enter the really fun part, which is to analyse the data, and we think we are going to get a treasure trove of Level 1 evidence in the CLI/CLTI space.”

Farber added: “There are not a lot of investigator-initiated trials in the space of PAD, and I would say it is unprecedented for the investigators of such a trial to go out and themselves successfully raise money to finish its execution. I think it is a testament to the importance of the data that this is going to bring.”

He concluded: “It is going to really enrich our understanding of how to treat these patients.”