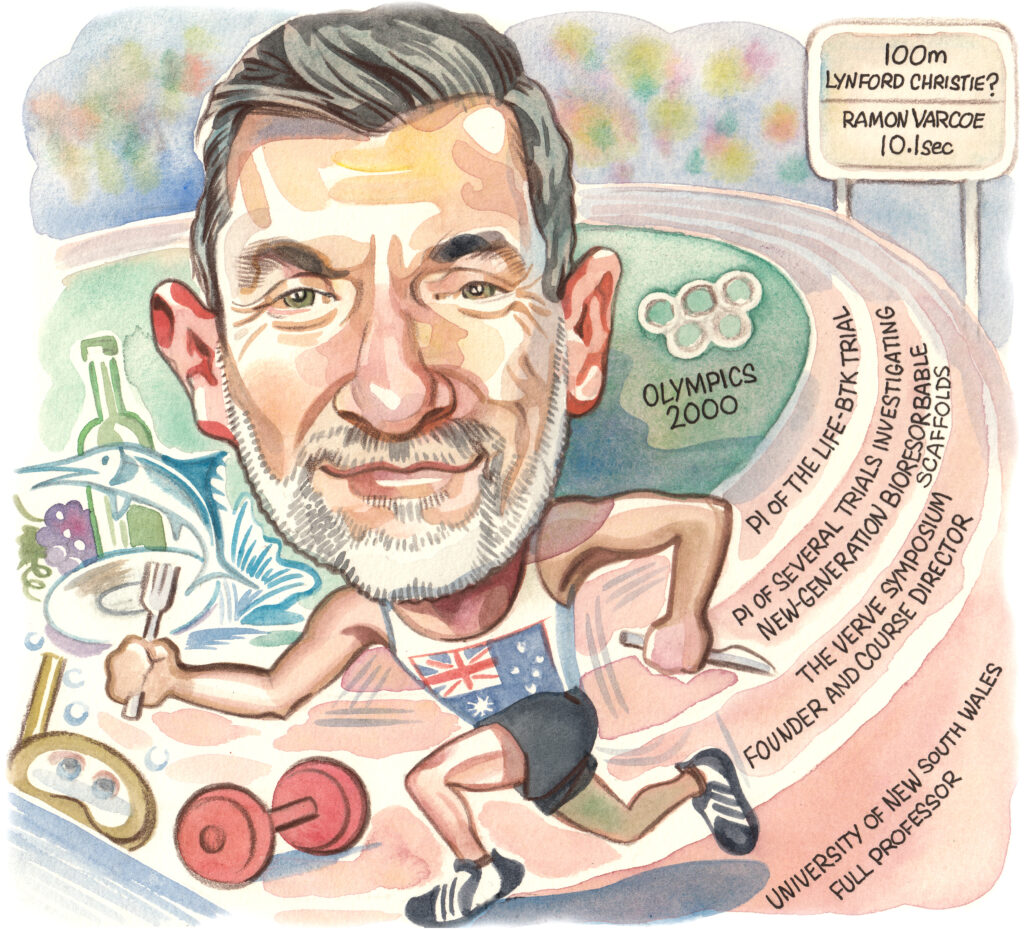

Following his presentation last year of 12-month results from the “landmark” LIFE-BTK randomised controlled trial, Ramon Varcoe (Sydney, Australia) speaks to Vascular News about this research as part of his wider career in vascular surgery so far. The vascular surgeon at Prince of Wales Hospital and full professor at the University of New South Wales also considers some of the biggest challenges currently facing the specialty, details his hobbies and interests outside of medicine, and reflects on how past experience in professional athletics has influenced his current work.

Following his presentation last year of 12-month results from the “landmark” LIFE-BTK randomised controlled trial, Ramon Varcoe (Sydney, Australia) speaks to Vascular News about this research as part of his wider career in vascular surgery so far. The vascular surgeon at Prince of Wales Hospital and full professor at the University of New South Wales also considers some of the biggest challenges currently facing the specialty, details his hobbies and interests outside of medicine, and reflects on how past experience in professional athletics has influenced his current work.

Why did you choose to pursue a career in medicine and what drew you to vascular surgery?

I come from a family with no history in medicine, so it surprised everyone when I chose that path at a young age. It’s hard to articulate why I was so strongly called to this career; sometimes, you just know things deep within.

Initially, I was drawn to psychiatry, which still fascinates me, but I ultimately prefer hands-on work, visualising anatomy in three dimensions, and solving problems. Vascular surgery, with its complex operations and the need to manage major blood vessels during critical moments, really appealed to me. At that time, the field was undergoing significant changes, shifting from traditional open surgery to an endovascular approach. I saw this as a perfect opportunity to be part of that transformation, where creativity and academic innovation were essential for advancing the specialty. I thrive in creative environments and have a passion for the scientific process.

Who were your career mentors and what was the best advice that they gave you?

I’ve had so many influential experiences that it’s tough to choose just a few. My earliest exposure to vascular surgery was with a pioneer in open surgery and transplantation in Sydney, John Frawley. He was a largerthan- life figure with a wealth of stories and an incredibly creative approach to surgery that was truly infectious. His inspiration shaped my early career.

In Adelaide, John Anderson was one of the early endovascular pioneers who demonstrated what’s possible when you think outside the box. At Westmead in Sydney, Professor John Fletcher became my first academic mentor, guiding me toward a lifelong passion for inquiry and a career in academia.

Geoff White, an endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) pioneer, and I collaborated on several conferences before his passing. The VERVE Symposium reflects much of what I learned while working alongside him. More recently, I’ve been fortunate to be mentored by Drs Michael Jaff and Peter Schneider, two giants in our field. They have both supported me and imparted invaluable lessons as my career has evolved.

What have been some of the most important developments in vascular surgery over the course of your career so far?

When I began my career in vascular surgery, it was primarily an open surgical specialty. EVAR was just emerging, and vascular surgeons rarely performed peripheral endovascular interventions, especially complex ones. We had large, dedicated vascular wards filled with dozens of inpatients, many facing piecemeal amputations that often led to belowknee or above-knee amputations. Our intensive care units (ICUs) were crowded with vascular patients, and large-scale abdominal surgeries, particularly open abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repairs, were routine, both elective and emergency.

That landscape has changed dramatically. We now admit only a fraction of those patients, and major amputations are rare at our centre. We often feel out of place in the ICU since we’re there so infrequently. The endovascular revolution has significantly improved patient care. Now, over 90% of my patients are likely to receive an endovascular-first procedure, with very few needing open surgery. This shift is beneficial for both patients and the specialty as a whole.

What are the biggest challenges currently facing vascular surgery?

I believe the biggest challenge we face now is how to manage the future of open vascular surgery. There are several key issues to consider. First, how do we ensure high-quality training for our trainees when open surgeries are becoming less common? Procedures like open abdominal aortic repairs, thoracoabdominal repairs, and distal bypass surgeries come to mind as complex operations that require a high level of technical skill. Unfortunately, these surgeries are rarely performed in most contemporary practices, and when they are, they often represent the most challenging cases. This makes training increasingly difficult.

Moreover, senior surgeons may feel less confident in supervising these procedures if it’s been a while since they last performed them. Over time, this could lead to newly graduated surgeons having less experience, further exacerbating the issue.

I’m also noticing a trend where vascular surgeons are positioning themselves as either endovascular or open surgery advocates. My perspective is that we need a balanced approach in our practice. Both endovascular and open techniques are valuable, and each may be the best treatment option for different patients at different times. I see them as complementary skills that every vascular unit should strive to provide at the highest standard.

At TCT 2023 you presented results from the LIFE-BTK trial, which were simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). What are your reflections on this trial one year on and what is next in the space?

This is one of the landmark randomised controlled trials in our field for several reasons. The endovascular treatment of infrapopliteal peripheral arterial disease has struggled with durability, and recent trials aimed at demonstrating that new technologies could provide better patency than simple angioplasty have largely failed. However, LIFE-BTK demonstrated a 30% risk difference in the primary endpoint, favouring the Esprit drug-eluting resorbable scaffold [Abbott] over angioplasty. This success led to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and subsequent commercial availability in the USA and parts of Asia, with more regions expected to follow. This development has the potential to revolutionise treatment options for patients with chronic limb-threatening ischaemia.

Twelve months later, we’re preparing to present the 24-month results at Vascular Interventional Advances (VIVA; 3–6 November). We will also share several related studies, including an economic analysis, a diversity, equity, and inclusion assessment, and an anatomical analysis using the Global Limb Anatomic Stating System (GLASS).

Additionally, several fast followers are emerging, with new scaffolds currently being evaluated in various phases of clinical trials, both above and below the knee. This has become an exciting area to watch and is definitely worth following.

You have been the lead investigator on several other trials. Are there any that have surprised you in their findings?

Our initial research on the previous generation of drug-eluting bioresorbable scaffolds revealed patency results in tibial arteries that surprised us all. This work paved the way for the development of the Esprit scaffold, which we utilised in the LIFE-BTK trial. The outcomes of that trial astonished even me. Despite my over 10 years of experience with these devices, I never anticipated a 30% difference in the primary efficacy endpoint. This finding highlights the effectiveness of these devices in the infrapopliteal circulation.

You are founder and course director of the VERVE Symposium—how has this meeting evolved since its first iteration 12 years ago?

VERVE has matured significantly over the past 12 years. What began as a small gathering of around 100 people at Coogee Beach has now evolved into the largest vascular and endovascular congress in the region. We draw faculty and delegates from across the globe, showcasing over 300 presentations and featuring more than 15 live cases. The event also has a vibrant social aspect, with a popular harbour ferry tour and a gala dinner with live music that everyone is welcome to enjoy.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

Although my practice now primarily emphasises endovascular techniques, I still have a passion for performing major open surgeries. I particularly enjoy open thoracoabdominal repairs and continue to use this approach for select younger patients. I recently completed one on a man in his late 30s under hypothermic arrest conditions. The procedure took 15 hours, but he was discharged within 14 days and has had an excellent outcome.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in medicine?

There are two quotes that resonate with me when reflecting on a career in medicine, and I believe they offer valuable advice for anyone considering this path.

The first pertains to choosing the right professional direction: “Find a job you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.” — Confucius.

The second emphasises the importance of service, which is a core principle behind pursuing a career in health:

“Service. Let this word accompany you throughout your life. May it guide you as you seek your purpose and responsibilities in the world. Remember it when you’re tempted to forget or overlook it. It may not always be a comfortable companion, but it will always be a faithful one, leading you to happiness regardless of your experiences. Keep this word not just on your lips, but in your heart. Let it teach you to do good simply and humbly.” — Albert Schweitzer.

You had a previous career in professional athletics—how has this influenced your career in vascular surgery?

Professional sports impart valuable lessons, such as the importance of hard work and dedication, the pursuit of excellence, and the drive to compete at your best every day. They teach you how to turn failure into immediate learning opportunities for future growth, which is essential for continual improvement. Additionally, sports highlight the significance of camaraderie and relationships. My experience as an athlete has greatly influenced my career, making me a better surgeon.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I have a passion for food and wine, especially when dining out while traveling in different countries. I also enjoy cooking at home and collecting wine to age in my cellar.

Water activities are a big part of my life; I love scuba diving, sailing, boating, and deepsea game fishing. Additionally, I collect art, which decorates both my office and home. Recently, I’ve taken up road cycling, which I enjoy around Sydney and during my travels abroad.