In a recently-published study, Jeremy Crane (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK) and colleagues conclude that a 3mm-long arteriotomy may be routinely utilised for brachiocephalic fistula creation in an attempt to limit the incidence of steal syndrome, while maintaining clinical patency outcomes. According to the authors, this is the first ever series in the literature of a 3mm arteriotomy.

“The arteriovenous fistula [AVF] is the modality of choice for long-term haemodialysis access,” the Journal of Vascular Access (JVA) paper begins. The authors cite lower rates of access-related infection and improved patient and access survival when compared to other modalities such as arteriovenous grafts or longstanding tunnelled central venous catheters as the reasons behind why the AVF is the most popular modality for haemodialysis access.

However, AVF formation is “not to be taken lightly,” Crane and colleagues warn, noting that dialysis access-associated steal syndrome (DASS) as an “important” and “potentially limb threatening” complication. They explain that the hallmarks of steal syndrome are symptoms and signs of peripheral vascular insufficiency within the limb distal to the AVF, which are often detected through a thorough clinical history and examination.

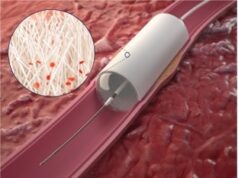

They go on to describe the feasibility of routinely fashioning a brachiocephalic fistula utilising a 3mm-long arteriotomy in an attempt to reduce the incidence of symptomatic steal syndrome, while maintaining clinical patency outcomes.

Crane and colleagues describe the study as a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected clinical data from a single surgeon. They detail that they included all patients who underwent brachiocephalic fistula formation using a routine 3mm-long arteriotomy within Hammersmith Hospital between January 2017 and March 2018 in the study. They note that primary outcomes included primary failure, failure of maturation, secondary patency, and steal syndrome.

Writing in JVA, Crane et al relay that 68 brachiocephalic AVFs were fashioned utilising a 3mm arteriotomy during study period, adding that the mean age was 60.5 years with 59% having a history of diabetes mellitus. The mean follow-up was 368 days, the authors write.

The authors report that primary failure occured in 10 (14.7%) of patients, and that cannulation was achieved in 67.3% of remaining fistulae within three months, rising to 87.3% by six months.

In terms of primary patency, Crane and colleagues note that this was 76% and 69% at six and 12 months, respectively. Secondary patency at the same time points was 91% and 94%, respectively. Finally, the authors detail that dialysis access steal syndrome was clinically apparent in three (4.4%) patients, with all cases being managed conservatively.

The authors acknowledge that the present study has certain limitations. Firstly, they recognise that steal syndrome is multifactorial in origin and not purely related to anastomosis calibre. In addition, “follow-up among the patients included in the study is limited,” Crane and colleagues write, adding that late presentations of DASS due to ongoing arterial and venous remodelling and subsequent increase in fistula flow may subsequently occur. They suggest that a randomised trial with clear documentation of venous and arterial diameter along with postoperative duplex ultrasound and haemodialysis access flow assessment would be useful.

Crane et al posit that comparison alongside other techniques such as the proximal radial artery AVF, particularly among patients deemed at higher risk of steal syndrome would be of interest. Nevertheless, they emphasise that a shorter length arteriotomy of 3mm “appears sufficient” to maintain fistula patency, while potentially minimising the risk of steal phenomena.