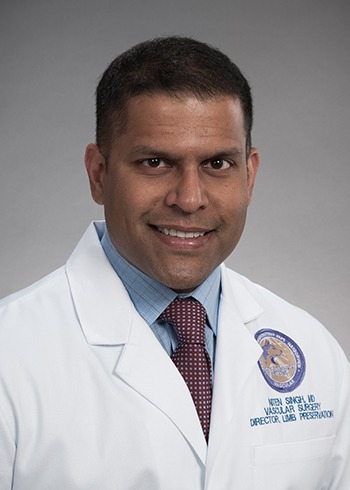

By Niten Singh and Benjamin Starnes

In the United States ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms account for 15,000 to 30,000 deaths per year. Open surgical repair had been the “gold standard” but was associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and with the advent of elective aortic aneurysm repair with endovascular techniques, this technology was transferred to the treatment of ruptured aneurysms.

In a recent meta-analysis of EVAR for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, Antononiou looked at observational studies, prospective and retrospective studies as well as any randomised controlled trials. The data were comprised of approximately 60,000 patients and the authors noted an in-hospital mortality of 30% in patients treated with EVAR and 42% in patients undergoing open repair (OR 0.56; 95%CI, 0.50–0.64; p<0.01). In addition, the morbidity was lower with regard to respiratory and cardiac complications. Interestingly, other studies have not revealed a benefit to EVAR in the setting of ruptured aneurysms over open repair; most notably the IMPROVE trial. Most of the studies with improved survival have adopted a strict algorithm approach to treating ruptured aneurysms.

At our institution, Harborview Medical Center, we are a level I trauma centre serving five American states with a geographic area of greater than 25% of the land mass of the United States. Because of widespread transport ability, we treat numerous vascular emergencies including ruptured aneurysms. We reviewed our outcomes for a five-year period from 2003 to 2007 and noted that our 30-day mortality was 57.8%. This prompted the creation of a “rupture protocol”. Our algorithm allowed for expedited transfer of patients directly to the operating room and involved the use of aortic occlusion balloons. Ruptured aneurysm patients underwent either EVAR or open repair dependent on anatomic suitability for EVAR. After initiation of this protocol we noted a decrease in mortality to 35.3% overall and 18.5% in those that underwent EVAR.n a recent meta-analysis of EVAR for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, Antononiou looked at observational studies, prospective and retrospective studies as well as any randomised controlled trials. The data were comprised of approximately 60,000 patients and the authors noted an in-hospital mortality of 30% in patients treated with EVAR and 42% in patients undergoing open repair (OR 0.56; 95%CI, 0.50–0.64; p<0.01). In addition, the morbidity was lower with regard to respiratory and cardiac complications. Interestingly, other studies have not revealed a benefit to EVAR in the setting of ruptured aneurysms over open repair; most notably the IMPROVE trial. Most of the studies with improved survival have adopted a strict algorithm approach to treating ruptured aneurysms.

This decrease in mortality is based on numerous aspects that have been created at our institution which include the following:

Coordination with our transfer centre – Our transfer centre will receive a call regarding a patient with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and will coordinate communication directly with the vascular surgeon on call. No administrative assistants or house staff are involved. After the patient is accepted, a medical record number is created so that the patient’s CT images are pushed electronically to our radiographic viewing system. Once the patient is accepted for transfer the surgeon makes one call to the operating room front desk to inform the charge nurse that a patient with a ruptured aneurysm is coming. Our hybrid OR which is nearly always prepared for ruptured aneurysms is prepped and upon arrival the patient proceeds directly to the operating room, only stopping to receive an identification band in the emergency room.

Wide selection of endografts – The patient’s CT has been reviewed and EVAR candidacy has been determined. If the patient is an EVAR candidate the grafts are already selected from a large in-house inventory. A wide selection of endografts is necessary to have a ruptured aneurysm programme. If the patient arrives to our centre with vital signs, all of the grafts are opened and flushed in preparation for immediate repair without delay.

Coordination with the anaesthesia and nursing team – Upon arrival the patient is placed on the operating room table, prepped and draped awake for an EVAR. Even if the patient is not an EVAR candidate we will access the femoral artery percutaneously (using the pre-close technique if stable) and place an aortic occlusion balloon (AOB) at the level of T-12 on fluoroscopy. The straightest iliac artery is chosen based on the CT for the aortic occlusion balloon. This balloon (Coda, Cook Medical) is placed via a 12F sheath that is 55cm in length (Cook Medical). If the patient is unstable or an open repair is required the balloon is inflated providing proximal control.

Comfort level with EVAR – Studies have revealed that institutions with higher volume have a significant survival advantage. In addition the operating team must be comfortable with EVAR as these procedures are often performed at night and off-hours. At Harborview Medical Center we have created a four-minute video that describes the organisation of the OR back-table and all of the wires and equipment required for the procedure. This video is available on our OR computer system and we encourage our OR staff to view this if they are not experienced with the procedure or have not done a similar case in a long time.

Perform an open repair if the patient is not an EVAR candidate – In a review of our ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm experience between 2002 and 2013 we looked at 215 CT scans and noted that 73% of patients qualified for EVAR and the main determinant was the aortic neck diameter and length. Iliac access was rarely an exclusion factor as other options are available. We did note that when EVAR was attempted in patients that were not truly candidates on review of the CT that there was a significant increase in mortality.

In conclusion, numerous strategies are involved to have a successful ruptured aneurysm programme and the creation of an algorithm and empowering all members of the team are key factors. A surgeon may be very comfortable with EVAR and ruptured aneurysm but if his anaesthesia team, nurses and institution are not, the programme will not be successful. In addition, as we move forward we are creating a mortality risk score based on preoperative variables from our large patient population that could potentially predict 100% mortality and allow us to counsel these patients for comfort care measures and potentially avoid an operation if the results will be futile. The above-mentioned factors are the foundation of our programme and we believe allow us to treat this complicated problem with a high level of success.

Niten Singh is associate professor of Surgery, and Benjamin Starnes is professor and chief, Division of Vascular Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, USA