Following a session on sexual misconduct in surgery delivered at the 2024 Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) annual scientific meeting (27–29 November, Brighton, UK), Ian Chetter (Hull, UK), Andrew Garnham (Wolverhampton, UK) and Mei Nortley (Oxford, UK) ask and answer common questions, discuss the pervasiveness of sexual misconduct within professional culture, and highlight what needs to change.

AG: How widespread is the problem?

MN: In September 2023, the Working Party for Sexual Misconduct in Surgery (WPSMS) published their groundbreaking paper demonstrating that sexual misconduct within surgery is rife and pervasive. Within the UK surgical workforce, 81% of men and 91% of women have witnessed sexual harassment. Two-thirds of women have been the target of sexual harassment and one-third reported being sexually assaulted. Over 10% of women had experienced forced physical contact for career opportunities.1 Whilst we struggle to digest the figures, it is automatic to comfort ourselves that this must be happening in other specialities—certainly not in ours. My conversations with vascular trainees across the UK would suggest otherwise, and experiences across Europe are reportedly worse.

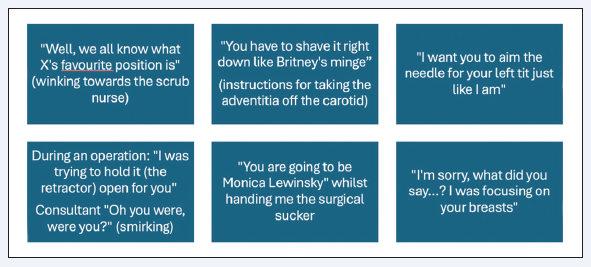

Figure 1 represents experiences reported to me. All targets were vascular trainees, and all behaviours carried out by more senior colleagues. As a young surgeon, arriving at work as a highly educated professional— expecting to be trained and treated as a colleague—it is degrading, humiliating, and demoralising to be spoken to like this. These examples represent the ‘mildest’—many more were removed as they are too disgusting to print.

IC: Please explain why misogyny and banter are unacceptable and should not be tolerated.

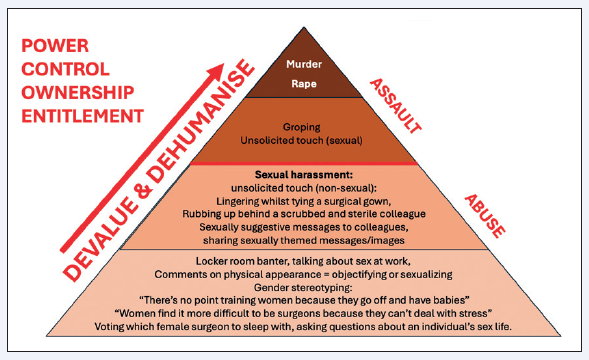

MN: I used to dismiss comments like those in Figure 1 thinking they “aren’t that bad” or “aren’t really hurting anyone”. Understanding the rape pyramid was pivotal for me. ‘Sexual banter’ involves objectification, sexualisation, misogyny and genderstereotyping and these reinforce the foundation of the rape pyramid (See Figure 2).2 This is a foundation of attitudes and belief that some individuals—often women—are of less value and are present, not as professional colleagues, but instead for sexual or menial purposes. It also contributes to themes of power, control, ownership and entitlement. During a recent tribunal, the panel acknowledged a doctor found guilty of sexual misconduct was “emboldened” by “banter culture” in his department.3 These attitudes and beliefs validate and justify all the behaviours towards the top of the pyramid, including sexual harassment, sexual assault, rape and even murder.

We all know an aspiring, hardworking young person entering a professional sphere—our siblings, children, nieces, nephews or grandchildren. The examples above don’t just represent vascular surgery. They represent a culture that pervades our society. Tolerating, permitting and contributing to comments which sexualise, objectify, gender stereotype or target minority groups, enables harm.

Understanding the rape pyramid makes it instantly clear that, as a professional community, we have a choice—we can choose to destablise the beliefs at the base of the pyramid— or maintain them. We can disable damaging attitudes and behaviours—or enable them.

AG: There is so much evidence on the impact of human factors—surely this must be affecting patient safety?

MN: Unlike other professions, instances of sexual harassment in healthcare occur during episodes of patient care—often during live operations. It affects our patients. There is consistent evidence that the most common factors contributing to safety events are human factors, leadership and communication.4 If surgeons are degrading, humiliating, and trying to touch their team members, they will not be focusing on their clinical practice. Moreover, those whom they degrade, humiliate, sexually harass or assault, will also struggle to focus on providing clinical care.

IC: Why is it crucial we address this problem as a matter of urgency?

AG: While it seems intuitive that we should take action, I think the topic can generate considerable discomfort for senior male colleagues who report fear of saying the wrong thing, ‘cultural misappropriation’, or that their contribution would not be valid. It is not unnatural to feel this way; however, female surgeons remain underrepresented in leadership,5 and so I don’t think we can afford to be ‘neutral’ or passive.

MN: Many women avoid this topic too. All of us have normalised these behaviours and many join in due to fear of marginalisation and a pressure to fit in. This culture is so pervasive that many can’t even identify it, and others feel a deep fear of highlighting themselves by speaking out, as it may affect their career progression.

Regrettably, inaction leads to inertia and inertia leads to enablement. There was a case within Oxford University Hospitals regarding a surgeon who sexually harassed and intimidated female trainees for over a decade. The words of one of the victims haunt me: “In the end it was a boys’ club. The standards you walk past are the standards you set. It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes a village to enable a sexual predator”.

Ultimately, this is our “village”, our vascular community, and it has to become our problem.

AG: How do we strike a balance between having a ‘fun’ team culture and maintaining professional boundaries in the work environment?

IC: General Medical Council Good Medical Practice (GMC GMP) guidance states: “You must not act in a sexual way towards colleagues with the effect or purpose of causing offence, embarrassment, humiliation or distress… [which] can include—but isn’t limited to—verbal or written comments, displaying or sharing images, as well as unwelcome physical contact”.

MN: I also find this definition easier and useful in my own interactions: “jokes or behaviour which are at the expense of, or considered offensive by, someone present are inappropriate”. Ensuring colleagues feel respected and psychologically safe at work should not deter a happy team culture; conversely, it generates one and allows humour.

IC: What should someone do if they accidentally touch someone at work?

MN: As a surgical profession, we often work in close quarters. But just as if you were to bump into someone on the street, if you accidentally touch someone, an open, timely acknowledgement and apology shows it was a genuine error and is respectful. “I’m so sorry—I didn’t mean to touch you—my apologies” works well.

IC: What should you do if you are in a consensual relationship with someone you are supervising?

AG: As a head of a school of surgery, I think it would be inappropriate to maintain a romantic as well as supervisory relationship with the same individual. Relationships will happen, but maintaining professional boundaries is crucial. The GMC guidance itself mentions being aware of situations with large differences in power levels between colleagues, or situations where training and career progression opportunities could be impacted.

MN: The Thames Valley Working group is cross-organisational involving NHS trusts, universities and ‘deaneries’ (now Health Education England). We propose any personal relationships should be declared—providing protection for all parties. Addressing any conflict of interests by removing yourself from educational or clinical supervisory roles linked to personal relationships is advised. It would not be appropriate for a teacher to be in a relationship with a pupil, nor a university professor with a student, nor a surgical trainer with their trainee.

MN: Where can you find relevant resources to learn more on the topic?

AG & IC: We would suggest starting with UK definitions of sexual harassment and sexual assault, GMC GMP guidance and Royal College of Surgeons’ guidance. The WPSMS also provides links to relevant resources. Locally it is important to know what your sexual harassment policies are and what processes are in place.

IC: What can we do to address the issue—both as individuals and leaders?

MN: As individuals, I think we need to appraise ourselves—both men and women. Reading the definitions of sexual harassment and assault was eye opening for me. You may realise that you have experienced sexual harassment or even sexual assault but not acknowledged it to yourself. You may realise that some of the things you have said or done, represent sexual harassment or sexual assault.

AG: We need to have challenging and awkward conversations and start educating ourselves on how to handle disclosures of sexual misconduct—and deciding how to act. A good starting point is to think:

“What do I need to do to safeguard the person in front of me?”

“If this was my daughter or son, what would I want to happen for her or him right now?”

We can also choose to challenge behaviours at the bottom of the rape pyramid. That can be anything from just not laughing, staying silent, or vocalising disapproval when comments are not acceptable.

MN: As leaders—if you don’t feel able to advocate, educate or speak up on these issues—facilitate. Get the voices we need to hear a place at the table where meaningful change can happen locally, regionally, nationally and politically. The VSGBI council made this a priority by introducing a code of conduct and putting this topic front and centre stage at the VSGBI annual scientific meeting 2024.

Currently, questions are being asked regarding the lack of institutional safety regarding sexual misconduct at every level. The need is urgent. At every stage of the work being done with my colleagues locally and nationally, we have found we are venturing into unchartered territory, but with that comes opportunity.

References

- Begeny C, Arshad H, Cuming T, et al. Sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape by colleagues in the surgical workforce, and how women and men are living different realities: observational study using NHS population-derived weights. British Journal of Surgery 2023;110(11):1518–1526.

- Alliance, Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action. Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance [Online]. Available from: http://www.vsdvalliance.org.

- Doctors.net.uk. Doctor “emboldened” by “banter culture” is suspended for sexual harassment [Online]. Available from: https://www.doctors.net.uk/news/doctor-emboldened-by-banter-culture-is-suspended-for-sexual-harassment. 2 August 2023.

- US Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Statistics Released for 2015 [Online]. Available from: https://info.jcrinc.com/rs/494-MTZ-066/images/Sentinel39.pdf.

- Skinner H, Burke J, Young A, et al. Gender representation in leadership roles in UK surgical societies. International Journal of Surgery 2019;67:32–36.

Ian Chetter is chair of surgery at Hull York Medical School, University of Hull (Hull, UK) and current president of the VSGBI.

Andrew Garnham is a consultant vascular surgeon at The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust (Wolverhampton, UK), immediate past president of the VSGBI, chair of the Confederation of Postgraduate Schools of Surgery, and head of the School of Surgery in the West Midlands.

Mei Nortley is a consultant vascular surgeon at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust (Oxford, UK), deputy director for undergraduate surgical teaching at the University of Oxford (Oxford, UK), co-lead for the Thames Valley Working Group for Sexual Misconduct and member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSEng) Sexual Misconduct Working Group.

Edited by Anna Pouncey, who is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) clinical lecturer, vascular specialist registrar, and member of the Working Group for Sexual Misconduct.