“We need to continue to build the scientific evidence base for what we do,” Kevin Mani (Uppsala, Sweden) tells Vascular News, underlining what he believes to be a key priority for vascular surgery in the years ahead. Research has been central to Mani’s career so far, forming a crucial part of his surgical residency and pathway into vascular surgery and culminating in his current role as professor and chief of vascular surgery at Uppsala University Hospital and chair of the Swedish Vascular Registry (Swedvasc). Mani also shares one of his most memorable cases to date, recalling the successful treatment of a young patient with complex aortic disease—an experience that for him exemplified the value of continued technological innovation and teamwork in vascular surgery.

“We need to continue to build the scientific evidence base for what we do,” Kevin Mani (Uppsala, Sweden) tells Vascular News, underlining what he believes to be a key priority for vascular surgery in the years ahead. Research has been central to Mani’s career so far, forming a crucial part of his surgical residency and pathway into vascular surgery and culminating in his current role as professor and chief of vascular surgery at Uppsala University Hospital and chair of the Swedish Vascular Registry (Swedvasc). Mani also shares one of his most memorable cases to date, recalling the successful treatment of a young patient with complex aortic disease—an experience that for him exemplified the value of continued technological innovation and teamwork in vascular surgery.

Why did you choose to pursue a career in medicine and later specialise in vascular surgery?

Medicine always felt like quite a natural choice for me and it’s something I have been interested in since childhood. When I eventually got into medicine and was exposed to various specialities, I found those that had the most impact on a patient’s life to be the most interesting. The acuteness of vascular surgery and the fact that it involves life and death situations drew me to the speciality.

Once I began my surgical career, I quickly realised that the area in surgery that was developing most rapidly and was the most fascinating was in fact vascular surgery. I did my training during a time where you still had to become a general surgeon and then go into vascular surgery as a subspeciality. Early on as a surgical resident I attended a course in vascular surgery and met Martin Björck, who was professor of vascular surgery at Uppsala University. He was the one who really opened the door to academic vascular surgery for me and was pivotal in those early days in terms of involving me in research and helping me to enter the speciality.

Were there other mentors in the early days of your career?

Anders Wanhainen was another fundamental influence during my residency—he was the supervisor for my PhD studies, and we’ve worked very closely together since, both clinically as well as academically. The way both Martin and Anders approach vascular surgery from a scientific perspective is something that has guided me in my practice.

Later, following my residency in Uppsala, I moved to London and worked with Peter Taylor, who was a true global star of thoracic aortic disease and thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), and Rachel Bell, who was the clinical lead at Guy’s and St Thomas’. They were two important mentors through those formative years of training and becoming a vascular surgeon. Rachel’s approach to honesty with the patients and the management of complex patients who are in life-threatening situations when you have to make hard decisions about what to do and what not to do, is something that I have always aspired to implement. I find it interesting how those mentors continue to affect one’s practice many, many years down the line. It’s an inspiration to think that now, I can potentially have the same effect on others!

It’s nice to be able to keep in contact with all of these mentors at international meetings such as the Charing Cross (CX) Symposium. Over time, these mentors also become close friends.

What have been some of the most important developments in vascular surgery over the course of your career so far?

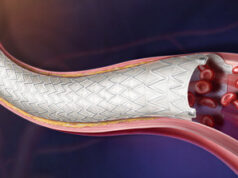

A key development has been the expansion of endovascular surgery into new fields. In the aortic field, for example, there has been significant progress in minimally invasive treatments for the thoracoabdominal aorta and the arch, which has been life-changing for patients.

Taking it one step back, in Sweden, and in fact this was probably the case internationally, the active involvement of vascular surgeons in endovascular surgery happened during my early years of training. That completely changed what we do and how we regard vascular surgery. When I started my training, there was a lot of discussion about vascular surgery not surviving the next 10 years, but it has gone from being an open surgical speciality with dire prospects, to becoming this thriving area where there is a massive force for innovation and constant improvement.

In my clinical practice, I’m still amazed by what we can do to help patients with novel endovascular techniques. And these are still progressing, leaving patients better off after their repair or able to recover and get back to their normal life more rapidly. When it comes to the arch and the thoracoabdominal aorta this has been particularly transformative. Patients that were regarded as “untreatable” some years ago, e.g. with aortic rupture in a challenging re-do field, can now be salvaged with innovative use of available stent-grafts with various tailored modifications.

What are the biggest challenges currently facing vascular surgery?

One of the main challenges for vascular surgery in 2024 and beyond is that we need to continue to build the scientific evidence base for what we do.

Being a speciality that has a very strong innovative side to it, we need to continue to show that what we do matters and makes a difference. This is particularly important in an environment where there is competition for money in healthcare. We need to remember that while innovation is fantastic and is of great benefit to patients, it also gets us under fire sometimes in terms of whether modern techniques are durable enough, or better than the alternatives. There have been areas where we have been too quick in adapting new technology that did not show benefit or stand the test of time. We should be cognisant about the fact that we need to have evidence for what we do.

We must continue working on building that evidence base so that we can continue to incorporate innovation into our clinical practice.

As the chair of Swedvasc, could you comment on the benefits of registry data in vascular surgery?

I had the privilege of getting involved in registry research early on through my mentors. High-quality registries that capture the practice of vascular surgery in a country or a region are valuable sources of data to various types of studies. This includes epidemiological studies, which assess what we are treating, how we are treating it, and what the trends are; and outcome studies, which assess the results of different treatments that we offer to patients and the patient selection for these treatments. Nesting randomised trials into registries is another powerful tool, and registry-randomised studies are increasingly used to evaluate new devices and interventions.

Vascular surgery is a field that deals with various low-incidence diseases—not necessarily the rarest diseases in the world but rare enough to be difficult to study in randomised controlled trials. Swedvasc and international registries in Vascunet have contributed significantly to the vascular surgery evidence base, with data now available on the management of various scenarios including infected grafts and ruptured internal iliac aneurysms.

We have been able to establish evidence for new technologies (e.g. endovascular aneurysm repair [EVAR] for infected aneurysms), as well as the threshold for repair for some of the pathologies involved, in studies that would be extremely difficult to conduct in any other way because we cannot find large enough cohorts of patients. The registry serves both to evaluate practice and identify best practices, as well as offer the possibility of spreading that best practice to new units and establishing evidence for new techniques that are being introduced.

There is a strong interest internationally for registries with the availability of new technologies for the management of big data. There is also an increasing number of good quality national registries established across Europe and indeed around the world. I believe we’ve only scratched the surface when it comes to large-scale registry data for both the evaluation of practice as well as for the monitoring of new device outcomes. Clearly there is a lot of future potential.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

When I was working for a year in New Zealand, we had a young patient with an aortic arch and a thoracoabdominal post dissection rupture. It was practically impossible to treat him with any traditional open surgical or endovascular technique.

However, thanks to the development of hybrid repair, the availability of modern stent grafts, and a very good team of vascular surgeons, radiologists and anaesthesiologists who would dare to go into an uncertain situation, we sealed off the rupture and saved this young father. He had initially been palliated until we found a reasonable solution for him, and he has lived for several years since the procedure. I think this is a case that really underlines the fact that modern technology allows us to do certain procedures that were not possible some years ago, and we certainly benefitted from having an enthusiastic team who were willing to take on new technology to save a patient.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in medicine?

Medicine is a unique craft; the patient encounters and the impact we can have on peoples’ lives is what makes it truly special. This is not a one-person job—the impact is best achieved in high-performing teams where individuals support each other aiming for the best result.

I would advise anyone looking to start a career in medicine to go with your gut feeling—find the area where you want to make your impact and find the team where you will prosper and thrive to make the most impact. To me, it is important to have fun at work. Vascular surgery is not a nine to five job—disasters happen 24/7 and patients need help unexpectedly—so this is an area where a certain level of passion and enjoyment is required. If you find a team that you enjoy being a part of, and you have a passion for saving lives and limbs, then vascular surgery is the speciality for you. In addition, I think an interest in innovation is beneficial if you’re going into vascular surgery. It’s been a speciality where innovation has been transformative, and there are still areas of innovation such as imaging, radiation-free practice, and artificial intelligence (AI) that are continuing to push the boundaries of what we can do.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I live in Sweden, so obviously we have proper winters and I enjoy skiing during that season, especially downhill. My kids also have the same interest. Then in the summertime, I very much enjoy dinghy sailing in the Swedish archipelago and spending time by the water with my family.