“I would say that the future is incredibly bright for cardiovascular surgeons,” Joseph E Bavaria tells Vascular News. The 52nd president of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), Bavaria first studied engineering before pursuing a career in cardiovascular surgery, starting as an attending surgeon in 1993 in time to partake in the endovascular “revolution” of the mid to late 1990s. Considering the future of cardiovascular surgery, Bavaria believes that advanced technologies and techniques will open up new possibilities in treatments, but stresses that such developments must be democratised. He sees training and education as one of the biggest challenges facing cardiovascular surgery, with societies across the world not recognising the huge commitment needed to the speciality, and sees the need for a wider recognition of the pre-eminence and importance of cardiovascular disease treatment.

Why did you decide to pursue a career in medicine, and why in particular did you choose to specialise in cardiovascular surgery?

The reason why I decided to go into medicine is a little circuitous. I had come from a family of engineers, and my father’s approach to life was, ‘no matter what you want to do, go to engineering school first and then do that’. At first I really wanted to be a lawyer, but two things changed this. The first was that my grandfather— who, along with my grandmother, lived in our house with us in Cincinnati, Ohio—was dying of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and that affected me a lot. The second thing was that our next door neighbour in Cincinnati was a general and vascular surgeon. I got to know him and ended up being influenced by him.

There were a couple of things that turned me towards cardiovascular surgery. Number one, I found that I was pretty good at the physiology and the medical part of the cardiovascular system, and it was very aligned with my engineering background in that era, which was the 1980s. The second thing was that, every summer, I used to work at the hospital where the next door neighbour I refer to above was a surgeon. The very last rotation I did there was in cardiovascular surgery and I was just fascinated. At that point I decided to go into cardiovascular surgery.

Who have been your career mentors?

I have had a number of career mentors. In chronological order, L Henry Edmunds, past chief of cardiovascular surgery at Penn Medicine and also editor of the Annals of Thoracic Surgery for 15 years, was my first mentor. As a resident, I did research on cardiac biophysics in his laboratory. My second mentor was probably the most important mentor I have had, and this was Timothy Gardner. He was chair of cardiovascular surgery after Edmunds, and he was the president of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS), which is a big deal—one of two really big global positions in cardiac surgery, the other being the presidency of the STS. Gardner was my mentor through my early career as a cardiac surgeon after my training and was very important.

There were a couple of others. On the vascular side was Ronald Fairman, who was not only a mentor but also a colleague. Fairman was the chief of vascular surgery at Penn and was the president of the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS). One non-local mentor would be Michael Mack, who is one of the most innovative cardiovascular surgeons around and was one of the inventors of the transcatheter valve revolution.

What do you think has been the most important development in cardiovascular surgery during your career to date?

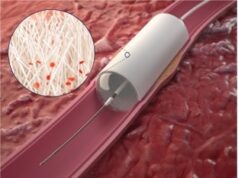

The endovascular revolution, so the concept of taking open cardiovascular reconstructive surgery and therapeutics into the endovascular and endocardiac domain, is probably the biggest thing there is in cardiovascular diseases as a whole, from a therapeutic standpoint. At the very beginning of my career, we did not have these things, but it came pretty quickly after I started in 1993 as an attending physician, and by the mid to late 1990s the endovascular revolution was beginning and on its way. Frankly, I am doing this interview because I was on the ground floor of that revolution and in two different domains: the first one was endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic disease, and the second one was endocardiac treatment of valvular heart disease.

How do you anticipate the field might change in the next decade?

I think that the continual march towards increasingly precise endovascular treatment and endocardiovascular treatment will continue. There is going to be a push towards treating areas that have not been able to be treated before, such as the proximal aorta, some of the more complex heart valves, and some of the more complex and anatomical arrangements within the human body including the aortic arch and the thoracoabdominal aorta. I think that is going to be a revolution in the next 10 years.

In addition, and this is a bit more specific, I think there is finally going to be recognition that type A aortic dissection is a total aortic catastrophe, not just a localised catastrophe, and that the treatment paradigm is going to have to include both an open and an endovascular solution in its entirety. I think that we are finally going to be able to do that with advanced surgical techniques and advanced endovascular techniques.

The other thing is that we are going to be very focused on decreasing stroke and decreasing cerebral complications from these procedures.

What do you think are the biggest challenges currently facing cardiovascular surgery?

One of the major challenges is the cost of technology. There are many new technologies and techniques to treat cardiovascular disease, but these are not available to most of the world, because they are very expensive. We are going to have to come up with solutions so that these incredible technologies can be applied across the whole world.

The second challenge relates to training and education. Cardiovascular surgery is hard. It is hard on your brain, your body and your time, and requires a certain dedication. Unfortunately, it seems like societies across the world are not valuing this commitment and as a result, the trainees coming through medical school today and through residency, they do not want to do it. Why would they want to do something like this if it is valued and paid at the same rate as anything else? We have a huge problem, and this is true in the UK and Europe as well as the USA, that is a shortage of specialists who can actually do this stuff.

I suppose the last challenge is organisational. Cardiovascular diseases are essentially neck and neck with cancer as becoming the most common diseases in humans above a certain age, and I am sceptical as to whether that is properly understood by administrators and politicians. We must recognise the pre-eminence and importance of cardiovascular disease treatment.

What are your current areas of research?

One of my main areas of research has to do with understanding the genetic basis of aneurysmal disease, so genetically-triggered aortic conditions, especially in the proximal aorta. This represents a huge knowledge gap that must be addressed. It is also really important because, unfortunately, it is not acquired disease, it is just fate, and it usually affects younger people.

The second area of research is the application of endovascular treatment into the proximal aorta. This is the biggest therapeutic area that we are working on.

The third thing is the recognition and then subsequent treatment of type A aortic dissection as a total aortic catastrophe. We are moving towards an understanding that at the index procedure and at the index part of the disease process you can make a big difference.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in cardiovascular surgery?

I would say that the future is incredibly bright for cardiovascular surgeons. It is a broad field and there will be something for anyone who is interested in this area from peripheral vascular surgery more towards the pure cardiac side. There is probably going to be a limited but real need for cross-trained individuals who are both cardiac and vascular boarded—these are going to be your “true” aortic surgeons who can deal with the entire aorta. That is something that we will need to deal with as a whole, global community in the future.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

Outside of work, I enjoy golf, travelling the world (I grew up in Europe), wine, which is intertwined with my love of travel. Also, while I am not a hunter, I enjoy trap and skeet shooting.