Jacques Busquet (Val d’Or Hospital, Paris, France) speaks to Vascular News about his life and career. A proponent of endovascular techniques—having co-founded the International Society of Endovascular Specialists (ISEVS) alongside Edward Diethrich—Busquet highlights the need to train the next generation of vascular specialists in “essential” open surgical skills as one of the most pressing current challenges in the field.

Jacques Busquet (Val d’Or Hospital, Paris, France) speaks to Vascular News about his life and career. A proponent of endovascular techniques—having co-founded the International Society of Endovascular Specialists (ISEVS) alongside Edward Diethrich—Busquet highlights the need to train the next generation of vascular specialists in “essential” open surgical skills as one of the most pressing current challenges in the field.

Why did you choose to pursue a career in medicine and what drew you to vascular surgery?

I come from a long line of medical professionals. My uncle was a general practitioner in Bordeaux, France, and both my father and grandfather, as well as my great uncle, were maxillofacial surgeons. My sister Anne, who is two years older than me, chose to study pharmacy with a specialisation in biology. So, medicine was very much part of my family heritage.

I also had the privilege of studying at the Université Victor Segalen in Bordeaux, a medical school with a national reputation and a deep-rooted history. Bordeaux has long been a hub for medicine, not only because of its medical faculty, but also as the home of the world-renowned Naval Health School, which trained doctors to work overseas.

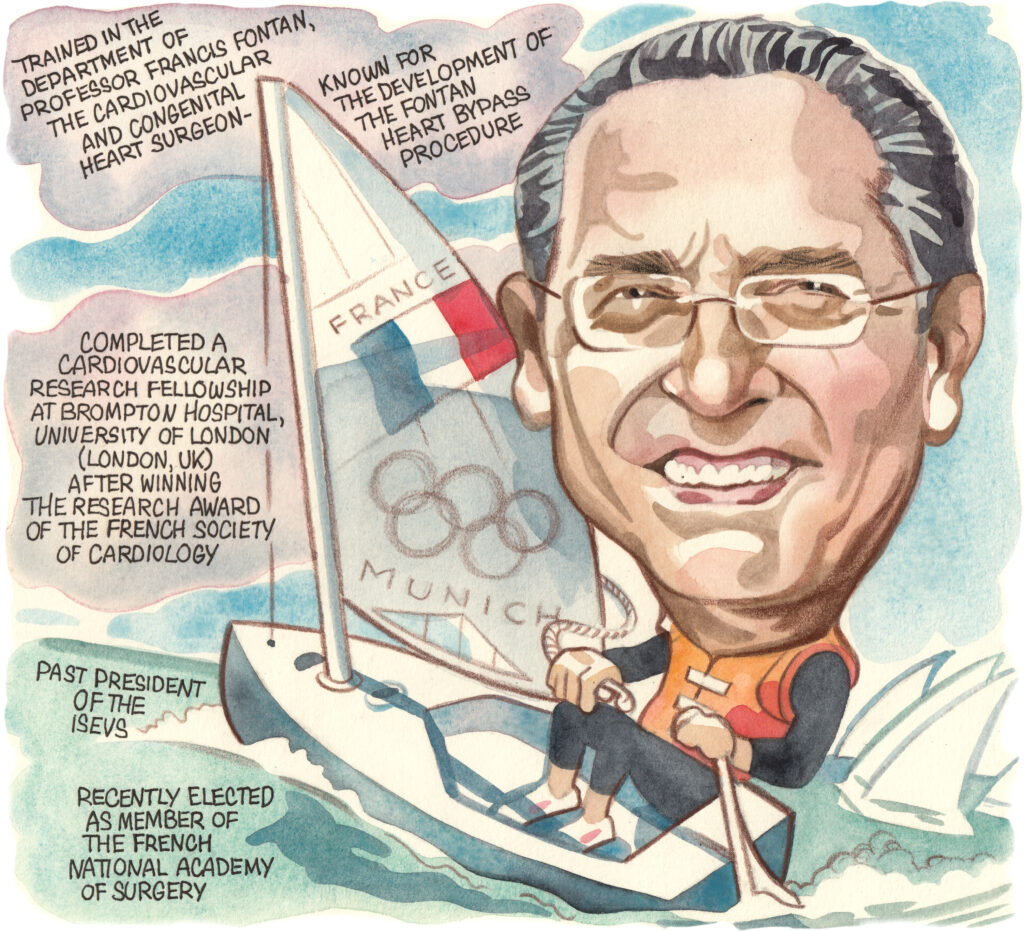

During my medical studies, which were interspersed with periods of Olympic training as part of the French national sailing team, I completed my military service at the prestigious Joinville Battalion, known for its elite athlete soldiers. After concluding this sporting chapter, I decided to pursue the highly competitive internat exam at the Bordeaux teaching hospitals, aiming to become a surgeon. Following 18 months of intense preparation, I was proud to place first among over 2,000 candidates.

This achievement allowed me to join the world-renowned department of cardiothoracic and vascular surgery led by Professor Francis Fontan—an experience that proved foundational for my career.

Who were your career mentors and what was the best advice that they gave you?

My first and most formative mentor was undoubtedly Professor Fontan. He is internationally recognised for developing the Fontan procedure, a life-saving operation for children born with tricuspid atresia or a single ventricle.

From him, I learned not only surgical technique, but also discipline: precision in the operating room, strict adherence to schedules, and an unwavering attention to the instruments and the craft. He also instilled in me a sense of striving for excellence, of always pushing toward the highest level of performance.

Another key mentor in my journey was Professor Robert Anderson, under whom I completed a clinical and academic placement at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London, UK. He was one of the most brilliant and prolific cardiac anatomists and pathologists of his generation.

Alongside his long-time collaborator Dr Su Yen Ho, Professor Anderson taught me how to structure a research project in the Anglo-Saxon academic tradition, and how to carry it through to publication in top-tier international journals with precision, rigour, and deep respect for the anatomical material we worked with.

My most influential mentor was Dr Edward Diethrich from Phoenix, Arizona, whom I first met in 1988 after an initial training period with Professor Rodney White at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in Torrance, USA. Dr Diethrich decisively steered my early career toward endovascular techniques at a time when many of our senior mentors saw little future in them. I had the privilege of participating in 27 consecutive editions of his renowned international congress.

Dr Diethrich and I had the opportunity to found the International Society of Endovascular Specialists (ISEVS) in Bordeaux in 1992, during our congress titled ‘Surgical approach to endovascular techniques: Opening of a multidisciplinary discussion’. I remained devoted to this dynamic, determined man of great natural elegance, whose scientific enthusiasm continuously illuminated all the years I was fortunate to spend by his side.

You were president of the ISEVS from 2011 to 2013. What were some of the highlights of your presidency?

Becoming president of ISEVS was a milestone for me, as I was one of the founding members back in 1992, during one of our first endovascular congresses in Bordeaux, my hometown. The society quickly grew, gathering members from all over the world, and later launched the Journal of Endovascular Therapy, which is now a leading publication in the field, currently led by Professors White and Kak Khee Yeung as editors-in-chief.

During my presidency, one of the main achievements was expanding our international network. We launched new chapters, including one in the UAE with Dr Omar Hallek and support from Dr Zvonimir Krajcer, and another in New Delhi with Dr Narendra Nath Khanna, who organised the Asia Pacific Vascular International Course, where I now serve as international ambassador.

We also developed a strong collaboration in Morocco thanks to Professor Amira Benjelloul and Professor Clifford Buckley, and we built lasting ties with leading vascular centres in China, in Beijing and Shanghai, where I had the privilege to perform a live aortic case at Fudan University Hospital.

I succeeded Professor Christopher Zarins from Stanford, USA, with whom I developed a lasting friendship, and I was followed by Dr Donald Reid from Glasgow, UK, a devoted student of Dr Diethrich and current president of the Arizona Heart Foundation, continuing the legacy of our mentor.

What have been some of the most important developments in vascular surgery over the course of your career so far?

At the end of the 1980s, traditional open vascular surgery was still at the forefront, while endovascular techniques were largely limited to coronary balloon angioplasty, which had only been introduced a few years earlier following Andreas Grüntzig’s invention in 1976.

Several international teams played a key role in the development of peripheral endovascular procedures, in my view. These included the UCLA Torrance team led by Professor White, the Arizona Heart Institute with Dr Diethrich, the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital with Jim May and Geoffrey White, the Ochsner Clinic with Christopher White, the Buenos Aires Vascular Institute with Professor Juan Parodi, the San Antonio hospital in Texas with Dr Julio Palmaz, and the Montefiore Hospital in New York with Professor Frank Veith.

Among them, Dr Palmaz, the inventor of the eponymous stent in 1986, and Dr Parodi, who pioneered endovascular exclusion of aortic aneurysms in 1990, stand out as two major figures who helped spark the endovascular revolution in vascular surgery. Their active collaboration marked a turning point in our field on a global scale.

What are the biggest challenges facing vascular surgery?

Since the endovascular revolution began in the 1990s, vascular surgery has become well established in modern centres, both in terms of techniques and decision-making. But I see two main challenges for the next generation.

First, we absolutely need to maintain training in open surgery—for bypasses, endarterectomies, and revascularisations, which young surgeons are doing less and less frequently, often preferring endovascular techniques. Yet, open surgery remains essential in certain cases where endovascular approaches reach their limits, such as instent restenosis or stent migration. Teaching hospitals must preserve this know-how for the future.

Second, there’s a financial challenge: the high cost of advanced endovascular devices makes access difficult in some countries. Without proper funding or reimbursement systems, we risk creating a two-tiered healthcare system, where some populations are left behind.

How has your background in competitive sport influenced your surgical career?

My father introduced me to competitive sailing, which I pursued at the highest level. I joined the French national sailing team in 1971 and participated in the 1972 Munich Olympic Games.

Over the years, I won several French championship titles, in both double and solo categories, as well as a European vice-champion title and victories in major international regattas like the Hyères Olympic Week.

This passion for sailing competitively has been more than just a sport for me—it has taught me how to navigate unpredictable challenges, a skill that has profoundly shaped my career in surgery. The ever-changing winds and shifting tides of the sea mirror the uncertainties of the operating room, where adaptability and quick thinking are crucial.

Beyond the water, I have completed more than 20 marathons across the world, including London and Boston marathons. Each race has been a journey of endurance, teaching me the virtues of perseverance, resilience, and mental fortitude. The discipline required to push through fatigue and doubt on the marathon course reflects the same unwavering determination I bring to my work as a surgeon.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

One of the most striking cases I encountered was a patient referred for what was thought to be a deep vein thrombosis in the left leg. But as soon as he arrived, we performed a venous and arterial Doppler, which showed no thrombus; instead, we discovered a giant abdominal aortic aneurysm. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram confirmed an enormous 16cm aortic aneurysm, along with a 12cm right iliac artery aneurysm.

We scheduled emergency surgery after obtaining informed consent from the patient and his family, given the significant operative risks. The procedure was carried out by two senior surgeons, assisted by a full anaesthetic and intensive care unit (ICU) team, with a cell saver in place for blood recovery.

Once we performed the midline laparotomy and opened the aneurysm, a large volume of blood escaped revealing a massive aortocaval fistula, about 10 by 6cm, which we closed immediately using a Teflon patch. We then performed an aorto-bi-iliac graft using an impregnated Dacron bifurcated prosthesis, successfully excluding both aneurysms.

The patient was admitted to the ICU in critical condition, having lost a significant amount of blood. Over the following 48 hours, the team worked intensively to stabilise him. He developed a post-transfusion hepatic jaundice and ‘white lung’ syndrome, requiring prolonged intubation and ultimately a tracheostomy.

After 30 days in intensive care, he recovered and was discharged. I still see him regularly, and he remains deeply grateful to our team. It is a case I will never forget, both for its complexity and for the outcome.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I have three principal hobbies: sailing, marathon running, and exploring antique markets. Family life is also very important to me. Even though I have been based in Paris for over 20 years now, I try to spend as much time as possible with my three grown children in Bordeaux.