A debate at this year’s European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) annual meeting (24–27 September, Kraków, Poland) centred on innovation in vascular surgery, with experts considering whether it will ‘change everything’ in the field. While Matt Thompson, chief executive officer of Endologix, underscored the inherently innovative nature of vascular surgery and the inevitability of technological advancement—he urged specialists to “safely adopt new technologies or become irrelevant”—vascular surgeon Jon Boyle (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK) championed a more cautious, patient safety-focused approach, highlighting past instances of innovation having caused harm.

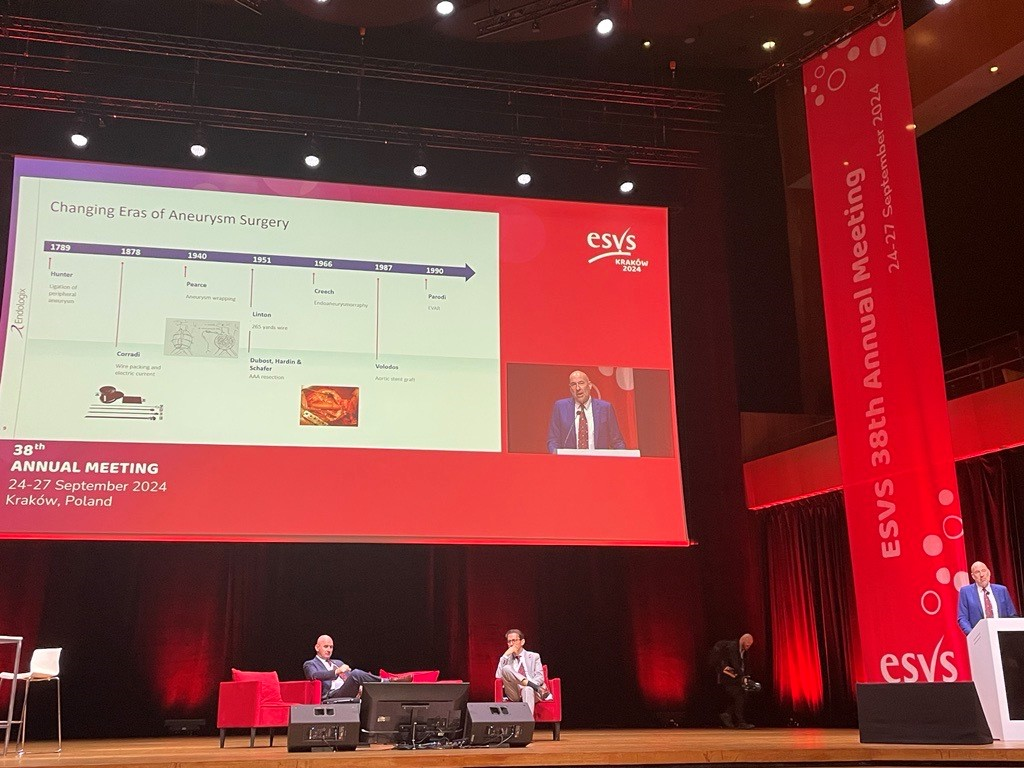

Thompson began by arguing that vascular surgery is, at its core, an innovative specialty. He cited several historical examples of disruptive advancements in the field, from John Hunter ligating peripheral aneurysms over 200 years ago, to the advent of open surgery and the subsequent endovascular revolution, all of which ushered in new and distinctive eras of treatment and fundamentally changed the vascular surgery landscape.

In the ongoing endovascular era, Thompson put forward, several innovations—including bioresorbable stents and non-invasive devices—have refined, or are set to refine, longstanding techniques and technologies. Indeed, the presenter said, there is “still room” for endovascular innovation despite the largely unchanging nature of its fundamental building blocks. However, these innovations will not, in Thompson’s view, ‘change everything’ in vascular surgery. Instead, he argued that the next paradigm shift in the field will be defined by the accelerated pace of technological change that is happening in the wider world.

Thompson argued that the pace of technological advancement in society has already led to “enormous” changes in how people live their lives. “It took 2.4 million years for humans to learn to control fire, but only 66 years to go from the first flight to humans landing on the moon,” he said.

The presenter continued that technology can change the world in ways that are unimaginable until they happen, noting, for example, that “switching on an electric light would have been unimaginable for our medieval ancestors”. This is only compounded by the accelerating pace at which technology is changing, he added.

Giving some examples of the technological advancements that are currently happening outside of vascular surgery, Thompson referenced the mRNA vaccines that were ushered in during the COVID-19 era at a pace that had before seemed inconceivable, to name just one.

So, the presenter asked, what do technological advancements in the wider world mean for vascular surgery? At present, he said, it is hard to know. He stressed that the only certainty is the inevitability of change.

“There’s going to be some technological advance that completely changes our practice,” Thompson posited, listing wearable technology, personalised and regenerative medicine, and artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning as just three technologies that have practice-changing potential. Thompson had a clear message here: adopt—safely—or be left behind.

“I’d submit to you that in a few years’ time, or a few generations’ time, we will have the same approach looking at the current practice of vascular surgery today and thinking it was about as barbaric as our medieval ancestors,” Thompson said in his conclusion. “I certainly don’t want that for me or my patients.”

“We’ve got to be careful how we innovate”

Putting forward a counter argument, Boyle stressed the importance of striking a balance between innovation and patient safety. In several instances of innovation, Boyle argued, “we’ve actually got it wrong—we’ve innovated, and patients have come to harm.” Boyle’s presentation highlighted a number of devices and techniques used over the last 20 to 30 years that have harmed rather than benefitted patients.

First, Boyle referenced data from the landmark EVAR-1 trial, noting that patients who were randomised to endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) “had far greater numbers of interventions out to 14 years” than the patients who received open repair.

Acknowledging the age of the EVAR-1 data as a weakness of his argument, Boyle subsequently moved on to newer EVAR evidence. Specifically, the presenter spoke on results from the VQI VISION study regarding the AFX graft (Endologix). The 2022 data, which illuminate reintervention and rupture rates with an early iteration of the device in the USA, were published by Goodney et al in the British Medical Journal.

“When we fix an aneurysm, we’re trying to do it to prevent rupture, but the early AFX graft had a near 40% reintervention rate at eight years and a 10% rupture rate at 10 years,” Boyle informed the ESVS audience, summarising the VQI VISION data. “So, 10% of the patients treated with this device ended up rupturing their aneurysm.”

In light of these data, Boyle remarked: “We’re fixing aneurysms, but we’re not really fixing them.”

The presenter also shared similar findings with regard to fenestrated repair. He commented bluntly that “fenestration means twice the likelihood of being dead at three years,” according to data from Vallabhaneni et al’s UK-COMPASS study, published in 2024 in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (EJVES).

Boyle subsequently presented data on peripheral arterial disease (PAD), citing a growing body of evidence showing that early intervention for claudication leads to worse outcomes.

Referencing an Australian study from Golledge et al, published in 2018 in the British Journal of Surgery, the presenter shared that patients with intermittent claudication who were treated early with endovascular intervention had a five-year amputation rate of 6.2% compared to 0.7% for those who received best medical therapy and exercise. “Early intervention for intermittent claudication with new devices led to a significantly higher amputation rate in this patient cohort,” he summarised.

The story is similar regarding carotid stenting, Boyle pointed out. “We’ve pretty much stopped doing carotid stenting in the UK,” he said, sharing that only around 250 such cases are conducted in the country every year. “The reason for that,” he explained, “is that for symptomatic disease, your relative risk of stroke and death following carotid stenting is 1.7 compared to carotid endarterectomy.”

Towards the close of his presentation, Boyle went back to Endologix, this time focusing on Nellix. “We got our fingers burnt with this device,” the presenter acknowledged. He recalled a sense of optimism in the early stages of using this device. “We all felt at the start this was a device that may change practice,” Boyle remembered. In the end, however, the presenter stressed that “a lot of patients came to harm as a result of being treated with this device”.

Sharing some data on the device from his centre in Cambridge—specifically from a 2021 EJVES paper by Singh et al—the presenter noted that, at six-year follow-up, only 32% of patients still had freedom from device failure and there were “quite a few ruptured aneurysms”.

In his conclusion, Boyle reiterated his central argument that “we’ve got to get the balance right—we need to innovate, but we need to do it in an environment where we can ensure our patients are safe”. The presenter continued: “Evidence-based, tried and tested techniques often result in better patient outcomes.”

A show of hands following the debate revealed a close result, with ESVS president Ian Loftus (St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK) declaring a narrow win for Thompson.