Nicolas Diehm says uniform endpoint definitions are mandatory to grant comparability of future endovascular studies

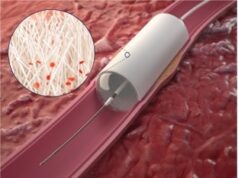

Endovascular therapy for the treatment of peripheral arterial occlusive disease was introduced in 1964 and has revolutionised treatment approaches to many vascular diseases with overwhelming speed.

Since then, a plethora of studies on technical improvements and innovative developments has been published.

These technologies, however, have developed at a pace critical scientific appraisal has been profoundly challenged to keep up with. Alarmingly, a main drawback of these studies is that they do not operate with uniformly defined endpoints thereby hampering a direct comparison of study outcomes across various trials difficult.

A pivotal publication on standards to report results of peripheral revascularisation has been published by Rutherford in 1986. Although these standards are widely accepted for surgical trials, this is by far less so for trials assessing endovascular therapy.

Some of the terminology that has been adapted during the transition from open surgical to endovascular treatment approaches needed adaptation. The term patency, for example, derives from surgical revascularisation literature and is used to describe the presence of uninterrupted flow as proved by findings of objective imaging modalities.

In recent years, we have witnessed an odd abuse of the term “patency” that has misleadingly been utilised to describe both anatomic and clinical outcomes.

First, there seemed to be a trend to report “clinical patency” with varying implications and of unclear definitions, which were particularly poorly outlined in ever faster appearing “rapid fire communications”.

Moreover, clinical outcome parameters, if they were cited, rarely assessed true functional changes after endovascular revascularization from a patient’s perspective.

Not only is it difficult for the casual reader to extract a balanced view from current reports, but the basis for valid evidence is sloppy.

The term “clinical patency” should be abandoned in future trials. Second, applying the term “patency” according to the surgical definition, high grade stenosis would still imply that the vessel is patent.

According to the TASC document, primary patency implies uninterrupted patency following a revascularization. As restenosis is a major drawback of endovascular therapy, however, it is mandatory to precisely quantify its extent to gauge the anatomic efficacy of various treatment approaches.

Thus, “patency” is insufficient as the sole morphological outcome parameter in the scrutiny of peripheral arterial endovascular approaches.

Therefore, the term “freedom from binary restenosis”, which has been widely applied in the coronary revascularization literature and is derived from quantitative serial angiography should clearly be added to the spectrum of anatomic endpoint definitions.

The DEFINE manuscript, a consensus paper by a transatlantic group of multispecialty physicians outlines many important parameters and suggests further important anatomic and functional clinical outcome parameters. It was published in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery in 2008 and is aimed at providing uniform definitions for future endovascular revascularisation trials.

The use of the latter is mandatory to allow for a direct comparison of various trials and hopefully will help to further underline the clinical usefulness of various endovascular treatment approaches.