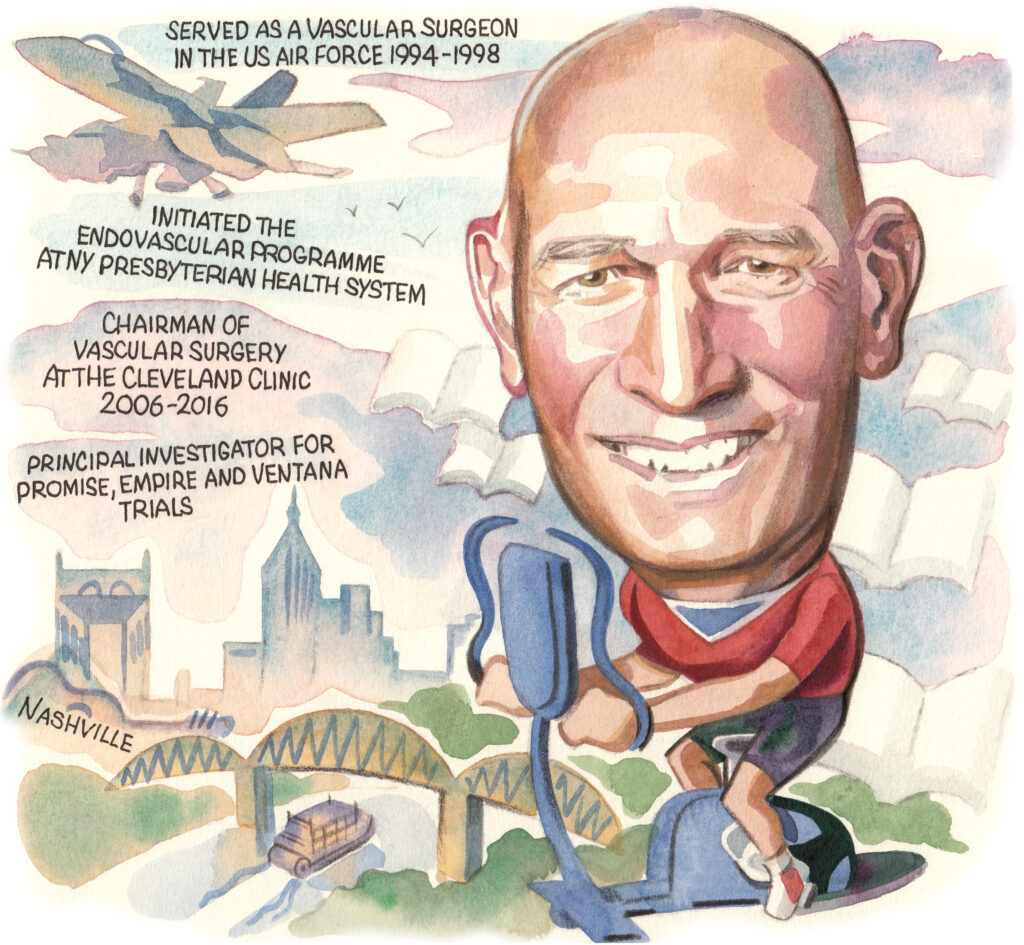

“The future of vascular surgery is incredibly bright,” Daniel Clair (Vanderbilt University Medical Center [VUMC], Nashville, USA) opines in this interview with Vascular News on his career in the field so far. Having always known he wanted to be a physician, Clair is now chair of the Department of Vascular Surgery in the Section of Surgical Sciences at VUMC. He details his keen interest and experience in trialling new innovations and technologies for the betterment of patient outcomes, highlighting in particular his ongoing work on deep vein arterialisation technology for limb salvage. Clair also considers some of the challenges and opportunities currently facing the specialty—pointing towards the future adoption of medical therapies—and advises aspiring physicians to look after their own health and wellbeing in order to be able to meet the demands and responsibilities of a career in medicine.

“The future of vascular surgery is incredibly bright,” Daniel Clair (Vanderbilt University Medical Center [VUMC], Nashville, USA) opines in this interview with Vascular News on his career in the field so far. Having always known he wanted to be a physician, Clair is now chair of the Department of Vascular Surgery in the Section of Surgical Sciences at VUMC. He details his keen interest and experience in trialling new innovations and technologies for the betterment of patient outcomes, highlighting in particular his ongoing work on deep vein arterialisation technology for limb salvage. Clair also considers some of the challenges and opportunities currently facing the specialty—pointing towards the future adoption of medical therapies—and advises aspiring physicians to look after their own health and wellbeing in order to be able to meet the demands and responsibilities of a career in medicine.

Why did you decide to pursue a career in medicine and why, in particular, did you choose to specialise in vascular surgery?

I honestly cannot remember a time I did not envision myself as a physician. There are no physicians in my family and my oldest sister is a nurse, but I had always believed I should be a physician. I planned to pursue a career in family practice and return to my home as a family medicine doctor, until I completed a surgery rotation in medical school at the University of Virginia (UVA). Long known for its training of primary care physicians, UVA was my first choice for medical school because of this history, but I truly enjoyed surgery and providing options to reverse urgent problems—a part of medicine I would not have experienced had I pursued a career in family practice.

During my surgery residency, I enjoyed many specialties, but recognised vascular surgeons established long-term relationships with their patients, much like primary care physicians, and I have always enjoyed these relationships with patients. Additionally, at the time I trained I also discovered I wanted innovation to be part of my career. I considered fellowship training in both minimally invasive surgery and vascular surgery for this reason, but eventually the combination of opportunity for innovation, lasting relationships with patients and the technical detail noted in vascular surgery were the features that attracted me to the specialty and have kept me engaged during my career.

Who were your career mentors and what was the best advice that they gave you?

I have been fortunate to have had a number of mentors over my career including John Mannick, who was instrumental in the establishment of vascular surgery as a separate specialty. He helped me understand vascular patients were the most frail patients in the hospital and that not all these patients could tolerate the large procedures we offered at the time. Anthony (Andy) Whittemore taught me the value of being technically skilled in the craft of surgery and Craig Donaldson and Mike Belkin taught me a great deal about educating vascular trainees. Ken Ouriel and Craig Kent provided insight into leadership and vision, and both taught me that striving for continued improvement would always prove valuable. Additionally, I have learned a great deal from individuals in industry and have seen how important the relationships between industry partners and physicians are for advancement in the field. Lessons about these critical relationships were taught to me most notably by John McDermott, Bob Mitchell, Simona Zannetti (a surgeon working in industry), Dave Deaton and Peter Schneider, all of whom I view as friends and mentors. And finally, some of my best mentors are former trainees who have taught me learning and teaching are bidirectional. I have been fortunate to have had an extensive list of wonderful trainees who have taught me a great deal, as I hope they have learned from me including John Eidt, Ben Starnes, Rich Cambria, Frank Pomposelli, Sean Lyden, Matt Eagleton, Zak Arthurs and Jocelyn Beach, along with many others. I do not know that there is an individual I have trained, from whom I have not learned something.

What have been some of the most important developments in vascular surgery over the course of your career so far?

Without question, the most important development has been the introduction and adoption of minimally invasive therapies. Having completed my formal vascular surgery training without any instruction in interventional therapy, my entire surgery and vascular surgery fellowship training included only open surgical procedures. During my military career, I began working with the radiologists performing angiography and interventional therapies and prior to initiating my surgical career at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, I was fortunate enough to have Norm Hertzer as my chair who clearly understood the value interventional therapies would bring to patients with vascular disease. Dr Hertzer allowed me three months to train formally with Bruce Gray, a skilled peripheral interventionalist who was instrumental in providing my training in performing endovascular procedures. Thanks to this preparation, I was able to start my career with over 700 peripheral interventions prior to offering this option to patients. It has been gratifying to see vascular surgeons adopt and embrace these technologies and this approach. It has strengthened our profession and has made vascular surgery unique in the ability to offer the spectrum of care for patients. More recently, it has been additionally critical to note that adoption of medical therapies to improve the cardiovascular health of our patients has been an added benefit for vascular specialists, and vascular surgeons have embraced this approach as well. I believe we will continue to see advances along this front that can reduce the impact of vascular disease on our patients and our society.

What are the biggest challenges currently facing vascular surgery?

Vascular surgery faces a number of significant challenges, including the training paradigm and the need to address the current method of training, the lack of adequate numbers of vascular surgeons, the increasing need for vascular care as the population ages—with the comorbid conditions leading to vascular disease continuing to increase—and the amputation crisis facing the global community. While these challenges will not be easy to address, there are a variety of approaches that can be taken to improve each of these, and therein lie the opportunities for the community of vascular surgeons. Vascular surgery is a relatively young specialty and as a maturing specialty, there are areas where we will need to look to other specialties for insight into methods to deal with these challenges. Orthopaedic surgery, ophthalmology and neurosurgery as well as cardiology, gastroenterology and oncology are all areas that have matured as specialties in ways that vascular surgery can take lessons from. The future for vascular surgery is incredibly bright and the opportunity is incredible. We have an excellent record of embracing technology, and helping to evaluate this technology to allow continued improvement in care. What I have seen in my own career is incredible and I am confident this has led to improvements in outcomes for our patients and I look forward to this progress continuing.

You are co-principal investigator of the PROMISE trials, which are designed to assess the LimFlow system. How do you hope this trial will change practice for patients with ‘no-option’ chronic limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI)?

The PROMISE trials have documented an ability to salvage limbs for patients previously relegated to amputation. My hope is that this will enhance options for patients and will continue to ‘move the needle’ toward limb salvage for more patients. While not all amputations are preventable, it is clear we can provide more limb salvage than we are currently. Any practice that really wants to provide limb salvage options needs to have this method available and the hope would be that this would reduce the number and rate of amputations from vascular disease. In addition, as with other technologies, I believe we are just seeing the first steps in the use of this approach and there will be increases in the application of and use of this approach. Amputation is an incredibly high price for a patient, their family and our society to pay—we should all be seeking ways to keep patients whole, functional and ambulatory.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

In a career spanning more than 30 years, there are a number of cases that are memorable, but perhaps one of my more memorable cases was the treatment of a large juxtarenal aneurysm with associated bilateral iliac artery aneurysms in a 93-year-old gentleman with contained rupture. He also had bilateral renal stenosis, mild renal insufficiency, and underlying pulmonary disease. This patient would never have survived an open operation. The case was treated with a hybrid procedure, using bilateral renal stents placed so the aorto-uni-iliac stent graft could be placed more proximally in the aorta; a cross femoral graft and an endovascular external to internal iliac artery bypass to maintain hypogastric perfusion in one hypogastric artery while excluding a large common iliac aneurysm—the contralateral internal iliac artery required embolisation; all of this performed after being flown to another country to perform the procedure on a patient of whom I had only seen non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan images. Thankfully, this patient did well and survived nearly another 10 years. This procedure, performed over 20 years ago, was something that could never have been even considered when I entered my career, but just 10 years after my training completed, a new era of therapy introduced by Juan Parodi provided a solution that has revolutionised the care of patients. We should all be grateful to Dr Parodi for his persistence and his courage in pursuing this innovative therapy.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in medicine?

Medicine is a career that will require your time and your commitment. It will give you an incredible opportunity to provide for your patients in ways you cannot imagine. The gratitude you receive from patients and families is rewarding and this will provide you with a wonderful sense of purpose. It is your responsibility to provide the best care you can for your patients and to assure you commit to caring for them as you would a member of your family. In order to do this effectively, you will need to care for yourself and for your family and assure you get the time you need and those close to you get the time they need as well.

It is more rewarding than you can ever imagine, but more demanding than you will understand until you are there. Plan time with family and for yourself throughout your career to ensure you have the energy to give to your patients what they deserve.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I have always had an interest in physical activity and I try to work out at least four to six days per week. I also enjoy playing golf and tennis with my wife Patty who has supported me through my career.

My other interest besides these physical activities is reading. I listen to books while working out, travelling to work and even while walking in the hospital. In this regard, I enjoy science fiction, biographies and autobiographical works, and I also enjoy reading about science outside of medicine.