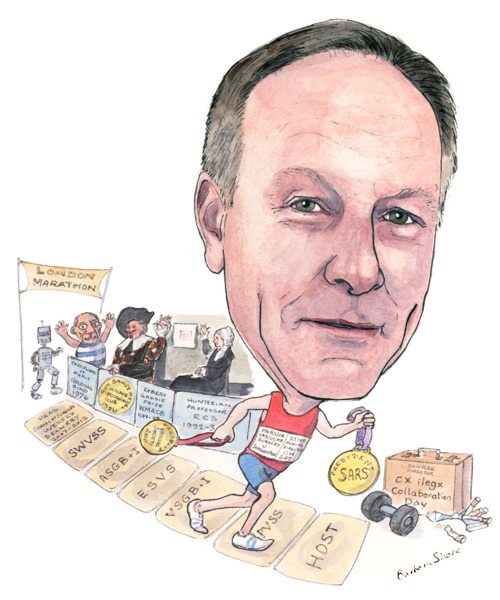

Cliff Shearman is professor of Vascular Surgery, University of Southampton, and a vascular surgeon in the Department of Vascular Surgery, University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust. A former president of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Shearman was involved in the process that culminated with the approval of vascular surgery as a new speciality in the UK. He tells Vascular News about his mentors, proudest moments, memorable cases and interests outside medicine – including running the London Marathon this year.

When did you decide you wanted a career in medicine? Why vascular surgery?

I was a typical school student who was interested in science and biology and did not have much idea of how to make this a career. No one in my family had ever done medicine and I must admit I had not got a clue at 17 years of age what it entailed. However, I had a relative who was a scientist and worked at the Medical Research Council and he got me a holiday job working in a research laboratory. I found it really quite bizarre that some of the incredibly bright people I worked with had spent their whole life studying a single molecule and everything revolved around this. I realised this was not for me. However, during the lunch breaks, I used to meet some of the medical students from the nearby medical school and I soon realised that clinical medicine was what I really wanted to do. I started medical school just after the first heart transplants were being undertaken and cardiovascular surgery seemed to be the most important thing in medicine and I initially wanted to do cardiac surgery. However, by chance, I did a vascular surgery job just before I was due to start a cardiac training scheme and was hooked immediately.

Who has inspired you in your career and what advice of theirs do you remember today?

There have been a number of people and organisations that had a profound effect on me and my development. I still almost on a daily basis remember some of them and use the skills they taught me.

Having trained in London I left to work in the Birmingham Accident Hospital, which at that time was the only dedicated trauma hospital in the country. I worked for Peter London who had been instrumental in developing this unit and making the premier place to train in trauma surgery. He taught me the importance of attention to detail and how often it is the small things that make a difference to a patient’s outcome. He also impressed me on the value of letting colleagues know when you were grateful to them. Peter London was very formal and always used surnames to address the team. However, after a very busy weekend in which we had all worked pretty much flat out, he caught me eating breakfast on the ward which was not allowed. I thought I was in for a dressing down but he came and joined me and told me how impressed he was with my performance. I cannot tell how good that made me feel for months afterwards.

The person who had the biggest impact on my vascular career was Malcolm Simms, a very gifted vascular surgeon in Birmingham. It was, in fact, working for him which persuaded me that vascular surgery was what I really wanted to do. It was not just because he was good at his job, but he was probably the most enthusiastic person I had ever met in medicine and who enjoyed every minute of the job. I also learnt from him not to give up when things got tough and I hope that is something I have stuck with to this day. The time to consider all the challenges is before the beginning of an operation. Once you have started, the role of the surgeon is to overcome any unexpected obstacles to get the best outcome for the patient. He very much had the same attitude to long-distance running which he got me involved with and I still think there are a lot of similarities to surgery.

After four years as a consultant in Birmingham, I had a difficult career decision to make and for a range of reasons I moved to Southampton. At that time I think I was a fairly typical surgeon interested only in my own service and speciality area, but the chief executive of my new hospital arranged for me to be seconded to the King’s Fund, a management college in London. I spent over a year intermittently working there and to this day the skills I learnt in managing people and myself I think have kept me sane and still enjoying the job. Probably most importantly I learnt that if you really want to improve a service you do not do it working on your own and moaning about things.

What have your proudest moments been?

Undoubtedly, becoming president of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland in 2010. As a vascular surgeon, I had been a member of the vascular society all my career and it had had a major influence on most aspects of my professional life. For me it was a particular pleasure to be president in 2010 as a whole team of presidents and council members had been working hard to get vascular surgery recognised as a new speciality in the UK and there was a real energy in the society to achieve this at that time.

Vascular surgery as an independent specialty was approved by the Parliament in March 2012. How have the vascular surgery curriculum and its implementation developed since then?

Soon after the new speciality was approved in 2012 the training curriculum, which includes endovascular training, was approved by our General Medical Council. We recruited our first intake of trainees in 2013. We were really encouraged that 273 trainees competed for the 20 national training posts indicating that vascular surgery is still a popular career choice. We are just about to recruit our next year’s intake and again have had similar numbers of applications so the future is looking good.

How has vascular surgery evolved since you began your career?

To me the biggest change has been to see vascular surgery recognised as a vital clinical service. When I first started my career I think many hospitals reluctantly supported vascular services and many surgeons did some vascular surgery together with general surgery. Now, as a new speciality, with our own training programme and a major re-organisation of vascular services it seems that no hospital can manage without a vascular surgeon! Vascular services have been recognised as a major service, there is considerable interest in the improved outcomes we are seeing and it is top of the agenda in most hospitals.

What have your most memorable clinical cases been?

Obviously, when a complex case goes well, as a surgeon you get a real buzz. However, the cases I remember most and have the most impact on me are when things have not worked according to plan and over the weeks and months afterwards, you get to know the patient and their family well. Trying to repair a badly damaged iliac artery in a three-month-old was very humbling and the child had to return to theatre three times. At one stage I had to warn the parents their child may lose its leg. To see the parents having to deal with this, but not being able to get the bypass to work at first was dreadful. Surprisingly over the years I still see the child who has done well and the parents remain friends!

How do you see the endovascular field developing in the future?

Endovascular interventions have made a major impact on the treatment of vascular disease. However, to me they are still a fairly crude solution to the treatment of vascular disease and I cannot believe that in 10 years we will be delivering endovascular treatments in the same way as we do now. In the short term, I see the use of computer technology increasing. Computer models can already be used to predict individual patient outcomes. Robotic technology is also evolving, which can achieve many parts of the intervention without many of the human limitations. In the longer term, better understanding of the biology of vascular disease surely must allow more directed medical therapies to be developed.

Diabetes-related lower limb amputation rates are still high in the UK. How does your team in Southampton address peripheral arterial disease and diabetes in order to prevent amputations?

The pathway to reducing amputations is awareness of the problem and prevention by early intervention. Frustratingly, this does not need lots of investment or more vascular surgeons; it simply needs better team working across the community and hospital care. We showed many years ago that is simple to do this; it will reduce amputations dramatically and also save the service money. Despite this there is still a considerable lack of consistency about how to design diabetes foot care services in the UK.

You were one of the course directors of the CX ilegx Collaboration Day held at the recent Charing Cross Symposium in London. What were the highlights of this year’s course?

The venue was unbelievable and worked well but as always I was encouraged to see such a large audience attending the session. When there is so much to choose from in the programme it indicates to me how important people see this area.

Also at the Charing Cross Symposium, you won a debate advocating supervised exercise, smoking cessation and best medical therapy before any intervention (with 71% of the votes). How feasible is to implement this across the country?

It never ceases to surprise me that surgeons who can carry out the most complex operations imaginable find it difficult to introduce an exercise programme for people with claudication! Of course the reality is that many are not particularly interested. Exercise is highly cost-effective and for many patients it will allow them to avoid the need for intervention, but it does need to be enthusiastically promoted. Even for the sceptical vascular surgeon, a well-run exercise programme will mean that patients who get referred to them from the programme will genuinely need intervention.

What is your opinion about the publication of individual results from vascular surgeons (surgeon level reporting) in the UK?

It is now inevitable the surgeon specific outcomes will be published annually in the UK. I think it has been difficult for vascular surgery, who after cardiac surgery, have led the way and there have been some painful lessons learnt. However, now this becoming routine for all specialities I think it will be easier.

I do have concerns, however, that it will focus vascular surgeons on undertaking index operations that are reported rather than the provision of the overall service. The most onerous and busy part of my job is the emergency week and yet during that time, I may do no elective index operations. In a speciality such as vascular surgery where there is an enormous range of activities that vascular surgeons contribute to the service I think we will have to be very careful how they are recognised when looking at surgeon performance.

You have been involved with the training of young vascular surgeons. What skills does the vascular surgeon of the 21st century need to develop?

Enthusiasm and the ability to adopt new ideas. Much of what the next generation of vascular surgeons is taught as trainees will probably be obsolete within years. However, one of the joys of surgery is learning new technologies and introducing them into practice to benefit patients.

What is the most interesting paper you have come across recently?

Surprisingly it was not a paper on vascular surgery but one on how we adopt new technologies into surgery. Generally, compared with many other professions we are very slow at doing this and for things like computer modelling on the effects of intervention we are positively still in the Stone Age.

Outside of medicine, what are your interests?

Although a late starter I have always enjoyed travelling and experiencing new cultures and I have had a lot of opportunities to do that. I particularly like to understand the influence that art has had on society, and although I have no expertise in this area, being married to an art historian I am learning! I still run and find it helps me relax and think. Having not done a marathon for 10 years I ran the London Marathon this year. The painful lesson I learnt is that as you get older preparation counts for everything and with little training it took me over an hour longer than 10 years ago. Anyway, I will try again next to regain my former glory!

Fact File

Present posts

1999–present Professor of Vascular Surgery University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

1999–present Department of Vascular Surgery, University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust

2008–present Associate medical director, University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust

Qualifications

1976 BSc (1st class honours), Intercalculated Medical Sciences, London, UK

1979 MB BS, London

1983 FRCS, England

1989 Master of Surgery, London

Medical education

1973–1979 Guy’s Hospital Medical School, University of London

1980–1990 Postgraduate Education, Birmingham, UK

Posts held

Aug 1979–Nov 1979 House surgeon, General & Vascular Surgery, Guy’s Hospital, London

Nov 1979–Jan 1980 House surgeon, Cardiothoracic Unit, Guy’s Hospital, London

Feb 1980–Aug 1980 House physician, Lewisham Hospital, London

Sep 1980–Sep 1981 Senior house officer, Birmingham Accident Hospital

Feb 1982–Jun 1982 Senior house officer, Regional Neurosurgical Unit, Derbyshire Royal Infirmary

Jun 1982–Dec 1982 Registrar, Orthopaedics & Trauma, Dudley Road Hospital, Birmingham

Dec 1982–Jun 1983 Registrar, General Surgery, Dudley Road Hospital, Birmingham

June 1983–Dec 1983 Registrar, Paediatric Surgery, General, Orthopaedic & Neurosurgery, The Children’s Hospital, Birmingham

Dec 1983–Jun 1984 Registrar, General Surgery, The General Hospital, Birmingham

July 1984–Mar 1986 Registrar, General Surgery & Urology, Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham

Mar 1986–Jun 1988 Research fellow, Dept of Vascular Surgery, Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham

Jul 1988–Oct 1988 Registrar, General Surgery, East Birmingham Hospital

Oct 1988–Oct 1990 Lecturer/honorary senior registrar, Department of Surgery, University of Birmingham

Oct 1990–Apr 1994 Senior lecturer/honorary consultant surgeon, Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University of Birmingham

May 1994–Sep 1999 Consultant vascular surgeon/honorary senior lecturer, Southampton University Hospitals Trust