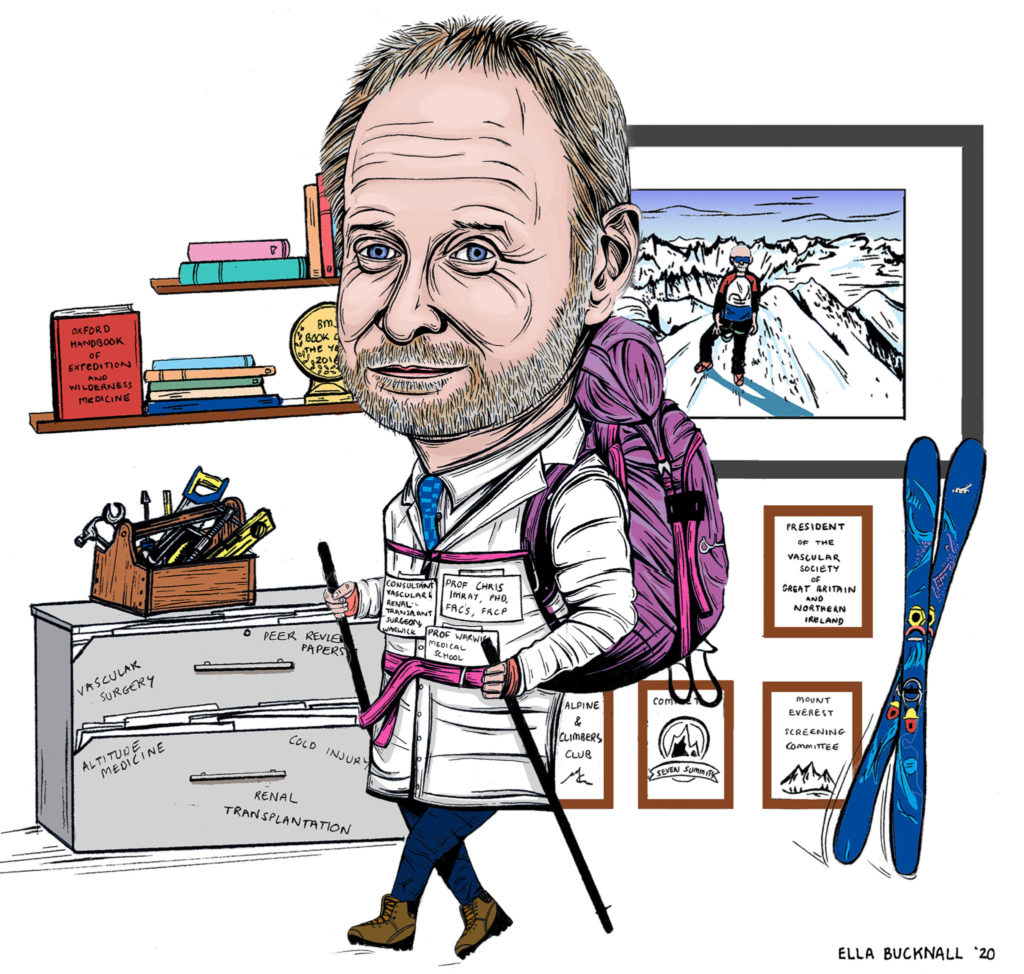

President of the Vascular Society for Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) 2019–2020 and avid climber Chris Imray discusses various aspects of his career. He considers how the field has changed, outlines his continued research into how the brain responds to hypoxia and ischaemia, and highlights a “particularly important” study into COVID-19 and vascular surgery.

President of the Vascular Society for Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) 2019–2020 and avid climber Chris Imray discusses various aspects of his career. He considers how the field has changed, outlines his continued research into how the brain responds to hypoxia and ischaemia, and highlights a “particularly important” study into COVID-19 and vascular surgery.

What led you to pursue a career in vascular surgery?

I trained at Charing Cross Hospital (London, UK) in the early 80s and within the first year or so, I was certain that I wanted a career in general surgery. The particular sub-speciality at the time did not seem that important. I am sure I was influenced by a number of surgeons but Keith Reynolds, an upper gastrointestinal tract surgeon stands out in my memory.

Who have been your mentors and what lessons did you learn from them?

Professor Roger Greenhalgh and Janet Powell at Charing Cross run a huge academic vascular practice and over the years have provided much crucial evidence on how aneurysms are best treated. Having good evidence to support complex interventions is a key component to safe modern surgery. Other standout professional mentors include Professor Richard Downing in Worcester, UK, whose technical prowess and quiet confidence impressed me enormously. Malcolm Simms, with his local anaesthetic distal vascular reconstructions stood out, as did Simon Smith, who taught me a lot of the principles on how to look after carotid surgical patients. Finally, Ross Naylor’s research has lead the transformation in safety of modern carotid surgery.

In the altitude world, Tom Hornbein (US anaesthetist and first to traverse Everest in May 1963), the late Many Cauchy (Chamonix physician and guide), Jim Milledge (respiratory physician) and Jo Bradwell (Birmingham immunologist) have both inspired me and influenced many of the decisions I made.

How have you seen the vascular field develop over the course of your career?

In the early 80s vascular surgery was very much an open speciality, where ‘heroic’ procedures were undertaken by heroic surgeons. At that time in my career, that seemed like a very exciting prospect and it was probably one of the reasons I was drawn into it. Gradually, we moved away from the individual hero to team-based approaches. The vascular surgeon is very much the conductor of the complex and interrelated orchestra. The introduction of minimally invasive endovascular approaches has dramatically changed the options that are open to the patient and medications have evolved considerably with the growth of statins and dual antiplatelets. Finally, and an area of particular interest to me, links aspects of high altitude physiology and understanding the cardiorespiratory factors. Trying to match up the magnitude of the surgery/intervention with the fitness of the individual patient has become key.

How do you anticipate the field might change in the next decade and what developments would you like to see?

I think the patient voice is finally being recognised as a key component in the decision-making, this is probably somewhat overdue. Integration of open, endovascular, medical treatments are becoming more important. Just as we have seen in many of the elite sporting teams, maintaining a high level of attention to small details is delivering the best results. I think we have also moved away from an individual-based service to a much more team-based approach. While I think developments on how to make the most of a team are probably going to be crucial in the future, I think understanding fitness of the individual and fine-tuning the best choice between an open, hybrid, or endovascular approach will become increasingly important. I think this will begin to help us as we improve on data collection, giving us a better idea as to which is the most appropriate personalised intervention.

In the last year, which new research paper has caught your attention?

The recently published COVER study, led by the trainee Vascular and Endovascular Research Network looking at the impact of COVID-19 on vascular surgery will turn out to be a particularly important study. I think we are likely to look back even in 10 or 15 years’ time and reflect upon the secondary impact that COVID-19 has had on our lives and particularly our high-risk vascular patients.

What are your current areas of research?

One of the features of my career to date is that although it has been somewhat unstructured, my enthusiasm and energy to explore new concepts and ideas has remained undiminished. Currently, I am particularly interested in fitness for surgery, multidisciplinary team working and my continued area of research is how the brain responds to hypoxia and ischaemia. I was very excited that, just prior to COVID-19, we managed to get 12 patients through a phase one pharmaceutical interventional study giving dexamethasone to try and prevent simulated high altitude cerebral oedema. Unfortunately, with COVID-19 this has all been put on hold, but I am hoping we will be able to get this up and running again shortly. We have previously shown that 24 hours of 12% oxygen can simulate MRI measurable cerebral oedema and the question here is whether or not intravenous dexamethasone can mitigate this, and by what mechanism.

How has your work in vascular surgery influenced your altitude research and vice versa?

I have been described as a translational physiologist using hypoxia and the perturbations that we can generate at altitude as a potential model for the ischaemia we see at altitude. My PhD is on hypoxic and ischaemic brain and much of my work has been around these subjects.

I am a strong proponent of cardiopulmonary exercise testing and this came out of research on Everest, undertaking VO2 max tests on the South Col (8,000m). In 2007, we had an unacceptably high mortality rate from open aortic surgery in my practice in the UK and I recall a fascinating discussion with the then chief medical officer, arguing the case that we should introduce cardiopulmonary exercise testing into our unit in order to risk-stratify the patients undergoing open surgery. His answer was that it was too complex an undertaking in a hospital, but I was able to respond with the fact that we had done this at 8,000m and the case was won. Subsequently, we have dramatically improved our results using this risk stratification method (along with many other units).

What advice would you give to someone starting their career in vascular surgery?

Firstly, I think this is one of the most exciting and varied specialties there is. I have been fortunate enough to travel all over the world using the research in both vascular surgery and extreme environments as the pretext to these excursions. I think it important that modern vascular surgery understands the different modalities available and is skilled in practicing them. I certainly did not plan much of my career, so I think that another piece of advice is to take opportunities as they occur. Having a positive and enthusiastic approach to the opportunities stands you in great stead. I think that having a good work–life balance is also the key to sustaining the energy and enthusiasm. I see many people who at the end of their career are not as enthusiastic as they originally were and I have been fortunate that my travel and research interests have kept me as enthusiastic as when I started out.

What are the biggest challenges currently facing vascular surgery?

I think COVID-19 will turn out to be probably the biggest and most impactful event in medicine for the next 10 or 15 years and it is difficult to see something more challenging than that, unless one considers climate change, which I believe is the biggest challenge currently facing humanity.

What have been the highlights of your of VSGBI presidency?

When Ian Loftus put the chain of office around my neck in Manchester in November 2019, my biggest worry was whether the provisional NICE guidelines on abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery would be accepted. The guidelines were finally released and, in my view, were a pragmatic solution to the difficult open/EVAR problem. Access to EVAR has turned out to ne a crucial adjunct in the COVD-19 crisis.

Following that, the rest of my presidency has been focused on the COVID-19 crisis. I have been extremely fortunate to work with a superb council. At the heat of the crisis, we were having weekly meetings on Zoom discussing how, first of all, we shut down vascular surgery in order to allow people to prioritise more urgent and emergency work, and then subsequently, the challenge of trying to restart. The council has been supremely supportive, and one of the most amazing reflections I have looking back on that is how they have worked together towards a common purpose in a collaborative fashion.

How do you like to spend time outside work?

As a teenager I was obsessed with climbing. I took a year out of medical school to work in Nepal and to climb in the Himalayas. Throughout my medical and surgical career, I have continued to climb. I managed to climb the highest summit on each of the continents (Seven Summits), completing the last in 2019. The odyssey had started unintentionally on our honeymoon on Kilimanjaro in 1988. I was fortunate that my wife shared both my interest, and understood my passion for, the mountains and although she sadly died in December 2019, I cannot thank her enough for the support she gave me and our family.