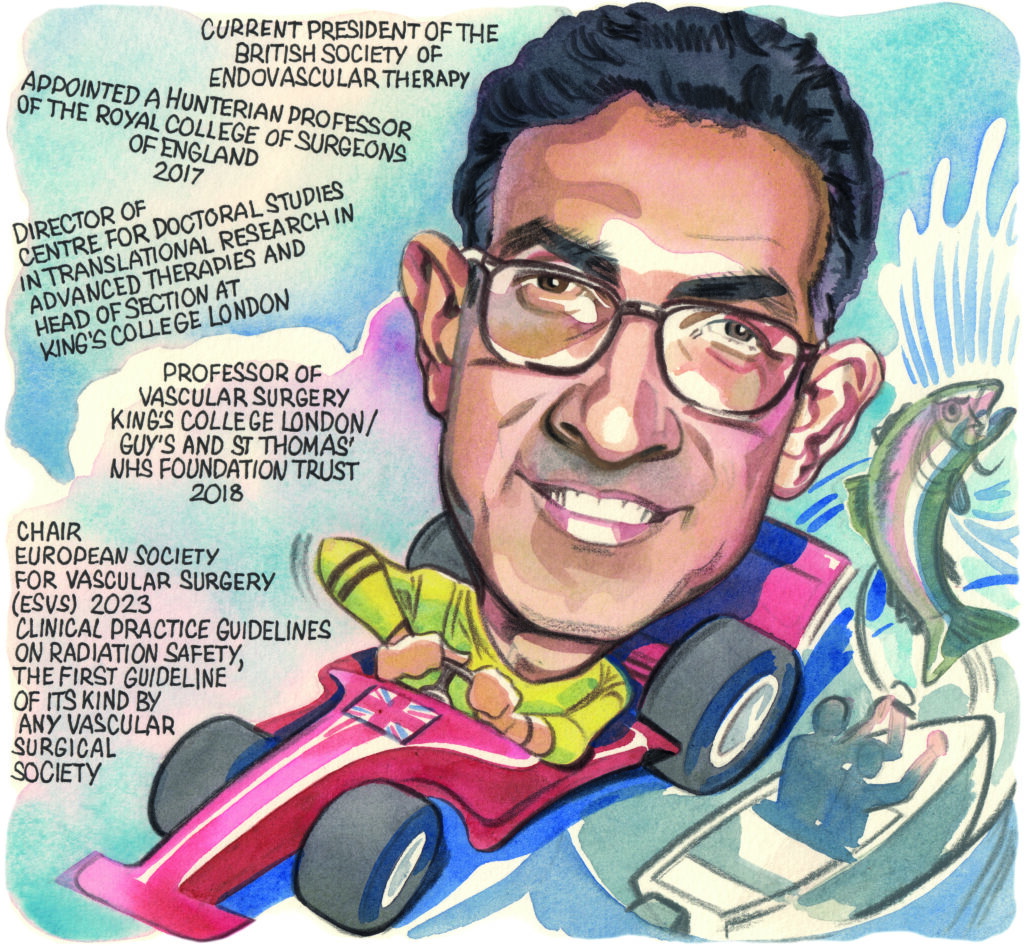

Interested in medicine from a young age, Bijan Modarai (London, UK) is now professor of vascular surgery at King’s College London and a consultant vascular and endovascular surgeon at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, where he co-manages one of the largest UK practices in complex endovascular aortic repair. In this interview, Modarai charts the course of his career in vascular surgery so far, highlighting his achievements as current president of the British Society of Endovascular Therapy (BSET), outlining some of his and his research team’s current work on radiation and DNA damage, and pointing to the inaugural Interdisciplinary Aortic Dissection Symposium later this year. Modarai also shares some advice for medical students, advising them “don’t listen to the naysayers” and to choose their mentors well.

Interested in medicine from a young age, Bijan Modarai (London, UK) is now professor of vascular surgery at King’s College London and a consultant vascular and endovascular surgeon at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, where he co-manages one of the largest UK practices in complex endovascular aortic repair. In this interview, Modarai charts the course of his career in vascular surgery so far, highlighting his achievements as current president of the British Society of Endovascular Therapy (BSET), outlining some of his and his research team’s current work on radiation and DNA damage, and pointing to the inaugural Interdisciplinary Aortic Dissection Symposium later this year. Modarai also shares some advice for medical students, advising them “don’t listen to the naysayers” and to choose their mentors well.

Why did you decide to pursue a career in medicine and why, in particular, did you choose to specialise in vascular surgery?

I was interested in medicine from a very young age. My father, an emeritus professor of chemistry, had always wanted to be a medic and thought this would be a great career so his influence may have contributed to this.

I became interested in vascular surgery in the first year of medical school. I liked the idea of operating on blood vessels and the fact that vascular surgery was a technical and holistic discipline. I found it an exciting discipline as a significant proportion of the work was done as an emergency and therefore success or failure was often instantly apparent. I did, because of this, worry in the early days that the demands of work may impact other aspects of life but in the end decided to do what I was passionate about and have never looked back.

Who were your career mentors and what was the best advice that they gave you?

I have had the fortune of several mentors who have taught me, led by example, and advocated for me. Kevin Burnand, my predecessor at St Thomas’ Hospital, taught me how to have exacting standards and care passionately for patients. He together with Alberto Smith, a prolific non-clinical translational scientist, supervised my PhD. Rachel Bell, who I met as a senior house officer when she was my registrar, taught me how to be a brave surgeon and, crucially, had my back in my first year as a consultant. Julian Scott suggested I apply to the British Heart Foundation intermediate fellowship scheme in 2010 and was always a sensible source of advice. Finally, Tom Carrell taught me complex endovascular aortic surgery and handed over the reins to the service at St Thomas’ when he left to found his startup company, Cydar.

What have been some of the most important developments in vascular surgery over the course of your career so far?

The application of complex endovascular techniques to every aortic territory has been a big advance and the fact that we are now on the cusp of incorporating the aortic valve into our repairs is highly compelling. We are beginning to see the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to inform case selection, planning and postoperative surveillance. Current algorithms are crude but in time I believe this approach will revolutionise how we treat the patient. We have also become better at searching for the evidence that supports our interventions. Hand in hand with this is a greater ethos of collaboration, where colleagues are open to joining forces nationally and internationally to accrue meaningful data.

What are the biggest challenges currently facing vascular surgery?

I believe our greatest challenge remains appropriate selection of patients for the plethora of procedures and devices that we can offer them. We are entering an era of personalised medicine that will be facilitated by intelligent data analysis. We are likely to find better ways of assimilating multi-modal data, including anatomical, physiological, and genomic, to allow better treatment selection and prediction of expected outcomes. Along these lines is the fact that most of the patients we treat as vascular surgeons are afflicted with systemic atherosclerosis and prolonging their longevity is a key remaining challenge. After aortic aneurysm repair, for example, our patients are succumbing to non-aortic diseases, including cardiovascular conditions that could be pre-emptively managed to prolong their life.

How do you hope the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2023 clinical practice guidelines will influence radiation safety in vascular surgery?

The guidelines—published in February 2023 in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery—were the first of their kind commissioned by any vascular surgical society and it was a privilege to cochair this endeavour with Professor Stéphan Haulon. First and foremost, the fact the ESVS commissioned these guidelines and the work they have done to promote them since being published has raised awareness in the field about the dangers of radiation exposure and what we, as operators, can do to protect ourselves and our patients. Our committee consisted of an expert interdisciplinary group and their synthesis of evidence in this space, in one document, provides an invaluable reference for our colleagues and highlights to institutions what safety standards they should be adhering to.

Could you outline some of your current research in the area of radiation safety?

As far as my group’s research is concerned, we have been fortunate enough to partner with the UK Health Security Agency and work with the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Chemical and Radiation Threats and Hazards at Imperial College London. We have important findings, which will be disseminated this year, pertaining to cytogenetic analysis in patients who have undergone endovascular aortic repair. Early indications are that patients show evidence of chronic DNA damage consequent to radiation exposure. Allied to that is a large-scale cancer incidence study we are engaged with that interrogates Hospital Episode Statistics data and the UK Cancer Registry to determine malignancy rates in patients after aortic repair. We hope that the latter project will determine whether the chronic DNA damage we have found has clinical consequences in terms of an increased incidence of malignancy.

What have been some of the highlights of your 2023–2024 presidency of the British Society of Endovascular Therapy (BSET)?

I have thoroughly enjoyed working with a dynamic council who have a “can do” attitude and together we have pushed through a number of initiatives with two recent examples being closer working with interventional radiology (IR) colleagues and the British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR) and a new research pump priming grant. BSET held an over-subscribed endovascular training course in March this year and it was a pleasure to teach a highly engaged and well-informed group of trainees.

The annual meeting, taking place 27–28 June (the National Vascular Training Day will be held on 26 June for vascular and IR trainees), has attracted the largest number of abstracts to date for any BSET meeting and will undoubtedly be a highlight with a number of high-profile international and national speakers attending. Finally, it has been a real pleasure to work with Jeanette Oliver who has expertly spearheaded the administration and organisational aspects of BSET for a number of years.

You are programme chair for the new Interdisciplinary Aortic Dissection Symposium. Could you outline the reasons behind setting up this event and what delegates can expect from the 2024 meeting?

There are very few meetings that are fully focused on aortic dissection, and we therefore thought it would be useful to put together this one-day symposium dedicated to the condition. According to the latest data, the incidence of aortic dissection is rising, and so it is a priority for vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons, interventional radiologists, and medical colleagues to optimise its management.

I envisage the symposium as an interdisciplinary forum in which to discuss the best practices for treating aortic dissection, including contemporary surgical and medical treatments. We will discuss upcoming trials, encourage debate and highlight real-life difficult-to-manage cases. This year the symposium is going to be held on 6 September at Bush House, a King’s College London campus, and we are fortunate enough to have several internationally recognised experts in aortic dissection speaking at the event. For more information, you can visit www.aorticdissectionsymposium.com.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

It is a privilege for a person to agree to be put to sleep and leave themselves in your hands with full trust. That focuses the mind for each and every case, but I suppose one remembers best the cases where you have to think outside the box and use a collaborative approach to achieve success. I remember a difficult emergent endovascular aortic arch repair that the team and I embarked on with trepidation and after some deliberation in a patient who was not a candidate for open repair. This was a difficult operation, including a cardiac arrest during the procedure that was expertly managed by cardiology and anaesthetic colleagues. The repair was successful, and it was hugely satisfying to give her more time with her family.

I also vividly remember being coached through my first significant operation, an appendicectomy, on Christmas Eve 1998 in my first year after graduating from medical school.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in medicine?

Don’t listen to the naysayers. Despite the pressures, medicine remains a very fulfilling career—a fulfilment that goes beyond what can be measured in monetary terms. Choose your mentors well. There will be lots of voices whispering in your ear as you navigate a way forward and these mentors will help you choose and focus on the worthwhile voices and advocate for you. Finally, remember that medicine is a multi-faceted career—it can afford you the chance of international exchanges, interacting with highly expert and interesting colleagues. You will acquire skills that can be applied to many other arenas in life. On a related note, I believe that as a community we should be doing more to promote surgery in medical schools, highlighting how it can lead to a rewarding career. This is necessary to ensure we have a strong talent pipeline and continue to attract those with potential to be the role models and key opinion leaders of the future.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I am an avid Formula One fan, and I have followed the sport for many years. As a youngster I spent a lot of time go-karting and I was a big fan of the Brazilian driver Ayrton Senna, whose career was cut short in a fatal crash at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1994. I believe he remains the greatest Grand Prix driver of all time. Last year I took my son to the British Grand Prix for the first time and we both had a wonderful time. I am also keen on fishing. I used to fly fish but more recently I have spent many enjoyable hours fishing by boat off the English coastline.