Described as “deliberately challenging”, the new time-to-treatment targets published by the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI), as part of the Peripheral Arterial Disease Quality Improvement Framework, have prompted a number of different measures in the UK for the treatment of patients with chronic limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI).

Speaking at the VSGBI’s annual meeting (27–29 November, Manchester, UK), Andrew Nickinson (University of Leicester, Leicester, UK) spoke about the potential benefits offered by a specialist, vascular limb salvage (VaLS) clinic, as well as missed opportunities for the timely recognition of CLTI within primary care. He said: “I think we are increasingly recognising that delayed diagnosis and management of CLTI are detrimental to outcomes, and there is a growing effort to try and reduce time-to-treatment after patients have been referred to us as vascular surgeons.”

Benefits of a limb salvage clinic

Focusing on the work done in Leicester for patients with CLTI, Nickinson discussed how “a nurse-led, open access, outpatient limb salvage clinic” has attempted to provide a one-stop assessment for patients. According to the speaker, patients referred into the clinic receive a detailed vascular assessment—including duplex arterial ultrasound—within the same day, before a decision regarding next steps is made “there and then” by a vascular consultant.

Moreover, it was said that these patients have access to dedicated outpatient angiography slots, “with the aim of this project being to treat patients in 10 days or less of initial referral”. In order to establish whether or not this limb salvage service can help to meet time-to-treatment targets, Nickinson explained that an investigation evaluating one-year amputation outcomes was conducted.

“To do this, we interrogated our prospectively maintained clinic database and included all patients who were managed with chronic limb threatening ischaemia or diabetic foot ulceration over a one-year period from the inception of the clinic (February 2018 to February 2019),” commented the speaker.

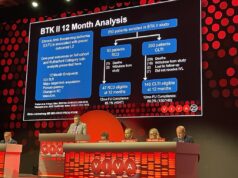

As part of the study, two comparative cohorts were formed; pre-clinic patients assessed prior to the start of the clinic (from May 2017 to February 2018), and also patients who were managed through alternative pathways, while the clinic was functioning. In terms of the latter group, Nickinson added: “This included for example, the people who still made it through to the elective outpatient setting.” Primary outcomes for the investigation were the rate of major amputation and amputation-free survival at 12 months.

“In total, we assessed 294 patients in the first year of the clinic, of which 222 had chronic limb threatening ischaemia or neuropathic diabetic foot ulceration. From the patients diagnosed with CLTI, approximately 75% went on to have a revascularisation procedure,” Nickinson revealed.

Regarding times to treatment, as Nickinson highlighted, the clinic was able to assess patients, on average, within two days of initial referral, and move them onwards to revascularisation within six days of assessment. “If you drill into those numbers further,” Nickinson continued, “this actually equates to five working days, given that the clinic does not work, at the moment, on weekends”.

“Looking at our primary outcome, which was major amputation at 12 months, those patients in the VaLS clinic had half the rate of major amputations compared to the other comparative cohorts, and this result was found to be statistically significant. The trend continued for amputation-free survival also and, in absolute terms, there was a 15% improvement, which was again statistically significant.”

Nickinson did note both the strengths and limitations of the data, as while this was “one of the few studies which actually provides comparative institutional data to compare our findings”, there is a possibility of selection performance bias in this cohort, as well as some crossover between these groups. Returning to the original question, Nickinson said of the clinic’s ability to improve time to treatment, “I think our early results indicate that yes, it can. What is more, this service potentially provides a blueprint for other trusts to meet these challenging targets. We have also shown that the clinic can improve amputation-related outcomes for patients”.

Missed opportunities for timely recognition of CLTI in primary care

Following his presentation on the success of a specialist limb salvage clinic, Nickinson turned his attention to what may be happening before patients reach the clinic and, specifically, whether or not a timely diagnosis of CLTI is being made in primary care. “The aim of this work was to investigate potential missed opportunities for timely recognition of CLTI in primary care,” the speaker told attendees at VSGBI.

To answer the question, Nickinson et al conducted a population-based cohort study utilising Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which includes approximately 11 million patients managed in 694 general practices across the UK.

It was explained that Nickinson and colleagues “identified all patients who underwent a major amputation, for either chronic limb-threatening ischaemia or diabetic foot ulceration in England, over a 16-year period (using hospital episode statistics (HES) data), and linked that to the CPRD in order to look at primary care consultations which occurred in the year prior to the patient having an amputation”.

Within each of the consultations identified, investigators also evaluated whether or not the patient underwent some form of cardiovascular assessment. Moreover, the primary outcomes of the study were the timings of a last primary care consultation and cardiovascular assessment prior to the patient undergoing an amputation.

Providing an overview of the findings, Nickinson outlined: “In total, we studied a predominantly male cohort of 3,260 patients with a median age of 72; as you would expect with a cohort like this, the one-year mortality rate was very poor (34%). What is interesting is that patients on average will seek a consultation with a healthcare professional in primary care 19 times in the year preceding their amputation, while over 30% of people will see someone over 25 times. Despite this, the prescription rates of best medical therapy continue to be poor, which is in keeping with the current literature.”

“When looking for missed opportunities, we identified that 67% of patients will consult a professional in primary care within that 30-day period prior to their amputation, but only 13% undergo any form of cardiovascular assessment during this time. Indeed, a quarter of patients will not undergo any kind of cardiovascular assessment in the primary care setting during the year prior to their amputation.”

According to the speaker, the data highlights that although patients are consulting the general practitioners and healthcare professionals within their community, it is possible that they are not undergoing the appropriate assessment.

A closer analysis of the results involved the stratification of patients depending on whether or not they had undergone a recent cardiovascular assessment (90 days before their amputation, or greater than 90 days). In the late cohort (greater than 90 days), it was identified that there was a higher proportion of patients from more deprived areas of the country, as well as significant, albeit small, difference in age, with the late cohort younger on average.

Concluding his presentation, Nickinson posed the question “do missed opportunities exist?”. In response, he affirmed that “this is a complex problem, and one solution potentially could be greater education, not just for our patients so that they recognise the symptoms and present, but also for those healthcare professionals who do not specialise in vascular surgery, to help improve recognition of CLTI”.

“That is a difficult task, as we know that up to 50% of patients presenting with CLTI have no history of PAD symptoms, but I do feel that we need to focus on those patients who may not fit that at-risk stereotype, including those of a younger age and from more deprived areas. This is important because, as we have established, major amputation carries a significant risk of mortality, and there is an opportunity to improve outcomes.”

“The research team would like to thank the George Davies Charitable Trust, who generously fund the VaLS clinic and on-going research,” said Nickinson in closing.