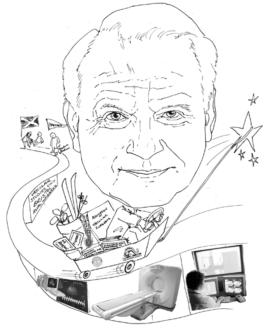

Vascular News speaks to vascular surgeon Mr Roger Baird on his academic career, his proudest professional achievements and how he “hitched his wagon to a star”. He also discusses his commitment to charity to work in his local area, as well as in the field of vascular surgery, and his advice to young people starting out in medicine today.

How did you first become interested in non-invasive vascular investigations?

Thirty years ago, my interest was aroused by the clinical assistance provided by two items of medical equipment. These were firstly in Bristol. One was an oscillometer, an air-filled cuff which was put round the ankle and measured pulsations, which I saw being used in Bristol, and secondly at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where a more elegant version called a pulse volume recorder was being used. Both of these items of equipment used an air-filled cuff around the ankle and movement of the air inside the cuff showed how strong the arterial pulsations were, which was better than feeling the pulses, which were all we had in the 1970s.

A major development was in ultrasound technology, ultrasound, which started at the end of the 1970s. There was rapid development in Doppler waveform analysis and in ultrasound imaging. At that particular time the technologies started to provide exciting answers to challenging diagnostic questions.

Nowadays, ultrasound imaging is wonderful and it has transformed pre-operative assessment from our early reliance on pulse palpation and the measurement of ankle pulsations. Huge developments are happening in diagnostic imaging, whether it is ultrasound imaging, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic imaging. In the last 30 years there have been vast developments. And, of course, in other branches of medicine, not just vascular, the improvements in imaging have made a huge difference. There is new and better imaging every year, which, although absolutely necessary, is of course very expensive.

What interested you about the academic side of medicine?

I was interested in it because it was innovative and changed the way we treat patients, as opposed to the apprenticeship system of training where you sit at the feet of the master and learn how to do it and you do it the way you were taught for the rest of your life. I wanted to be associated with the new developments that were coming in all the time.

Vascular surgeons have access to patients and undertake transitional research in collaboration with, in my case, very talented medical physicists who develop all these new ideas. We do new things to patients. This is translational research: you translate scientific theory into clinical practice.

Who have been the greatest influences on your career?

We all respect our teachers and my teachers in Edinburgh, where I started, were Archie Macpherson, Sir John Bruce, Sir James Fraser and Sir Michael Woodruff. In Bristol, Joe Peacock gave me great encouragement and support. When I came to do research, Bill Abbott in Boston, US, provided wonderful facilities and helped me to learn to write on research topics. These people were very formative for my career.

There’s a lovely quote that can help young people: “you want to hitch your wagon to a star.” I remember John Oschner of New Orleans in 1984 using that expression in his Presidential address to the American Vascular Surgery Society. It is as true for young people today as it was when I was young, which is that you see the stars and you want to be like them. Other stars I met and liked 30 years ago were the Texan pioneers, led by Michael DeBakey, Denton Cooley, Jesse Thompson (Carotids) and Stanley Crawford (Thoracic Aneurysms). In Britain, an early star of mine was Sir James Learmonth, who did a sympathectomy on King George VI. So there were these people who were stars and they did things that I wanted to do myself.

What have been your proudest professional achievements?

My greatest satisfaction has been my collaboration with the medical physicists in Bristol, in the Vascular Studies Unit, with Professor Peter Wells FRS, Professor John Woodcock and Dr Bob Skidmore. I was active with research fellows each year from 1976 to 1996. We wrote papers which and showed that ultrasound was as good as contrast arteriography using x-rays. Later CT scans and magnetic imaging came on the scene and needed evaluating. What we did in that 20-year period changed the ways British vascular surgeons investigated patients.

On the clinical side, in those 20 years we achieved better operative results and expanded the scope of the specialty to include all the big district hospitals as well as the teaching and research centres. I It was a team effort with radiologists, anaesthetists and intensivists. Patient selection, operative technique, and postoperative care improved. For example pain relief, with thoracic epidural analgesia in open aortic surgery, as well the intra- and postoperative restriction of intravenous fluids to avoid pulmonary oedema and the start of autotransfusion. These are now commonplace but in that 20-year period we were treating the patients better and we were rewarded by better results. It was an exciting time to be a vascular surgeon.

What would you say to someone just starting in vascular medicine today?

Young people today face different challenges, particularly of minimal invasiveness, whether that is endovascular or laparoscopic. In the next 20 years we’ll be able to fix people’s aneurysmal and blocked arteries with much less of a physiological insult, so that they have fewer complications and go home sooner. It’s not just vascular surgery that’s changing that way, other branches of surgery are evolving similarly.

Tell us about your work in fundraising for charity.

There are three strands to my charitable fundraising activities.

Firstly, as High Sheriff of Bristol in 2006, I led charitable fundraising in support of activities to keep young people from deprived parts of the city out of trouble. The money raised pays for youth workers who organise holiday, half term and weekend activities. In that way disadvantaged young people have a better start in life.

Next, my current local charity the Dolphin Society, raises money which helps housebound elderly people to be self-sufficient for as long as possible, in particular to assist them with their shopping and to help them maintain their independence.

Finally, as vascular surgery has been a big part of my life for 35 years, I am also on the committee of the Circulation Foundation, the fundraising arm of the Vascular Society of Great Britain, which raises funds to help with equipment or for a salary for a young researcher.