Vascular News speaks to Thomas Fogarty – surgeon, inventor and entrepreneur – about his distinguished career…

When did you first decide you wanted a career in medicine?

Up until the age of 17, professional boxing was my goal.

What turned you off?

I had approximately 40 fights; I was doing very well but my last fight wasn’t very clean. The individual was 23 and I was 17. It was a 7-round fight and the confrontation went 7 rounds and both my opponent and I just beat each other to a pulp. It was quite nasty. I broke my nose again and couldn’t see out of one eye. The opponent broke his right hand and also had a closed eye – they called it a draw. I thought, “if that’s a draw I never want to lose.” So I started to look for something else.

Were your family pleased with the change?

I think so. My father died when I was very young, but my mother was happy that I changed.

Why medicine?

Fortunately, as a preteen and teenager, I worked as an orderly at the Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio. At that time, I was able to get to know the doctors and became interested in what they did.

Any big influences?

My mentor was Jack Cranley, who was a vascular surgeon at the Good Samaritan Hospital. He was one of the first physicians to dedicate their practice purely to vascular surgery.

Why vascular surgery?

The technical aspects of cardiovascular surgery are a real challenge compared to other surgical specialties. It takes a more focused approach and complete understanding of pathophysiology.

Has your boxing been useful?

I think there’s a mental aspect to boxing that is similar to being a good surgeon – you have to be fully focused and go into the operating room convinced you’re not going to lose. A surgeon is concerned about not losing a patient and the boxer is concerned with not getting beat. As a boxer it doesn’t feel good – you lose your dignity and confidence, and the same is true when a surgeon hurts or loses patient.

Where there any pivotal moments?

Having good mentors – people that you like to emulate. I think that’s critically important for any professional group. Your attitude, perspectives and influence are determined by your mentors.

You’ve also been an inventor from an early age?

Yes, I did start at an early age. Inventing is about having the capacity to imagine and look at things not as they are, but as what you want them to be. Some people do not have the capacity to imagine.

Have you invented anything outside of medicine?

One of my first inventions was a centrifugal clutch. It used to be that you had to shift gears mechanically, and this was an automatic way to shift gears. It was taken up by Cushman motors, a manufacturer of small motors.

What about the business side? Do you have a

business brain?

People say I do and I probably do.

Which hat are you most comfortable with?

A physician who invents.

What is your proudest moment?

Being inducted into the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame for the balloon catheter. At the time I was inducted there were less than 100 inductees – Edison, the Wright brothers, Hewlett Packard – so it was a pretty elite award.

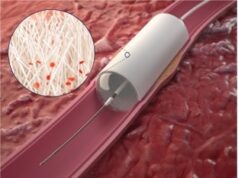

The balloon catheter was invented while I was in medical school. I used to be a scrub technician – the individual who hands the instruments to surgeons during surgical procedures. I saw many legs being amputated because they could not remove the thrombus. My mentor Jack Cranley challenged me to come up with something better than what we were doing. He convinced me that I would be a good doctor and that boxing was not the best way to spend my career.

Was the invention of the Fogarty catheter the beginning of endovascular surgery?

It was the beginning of less invasive surgery and of catheter-mediated therapy. We used to say the bigger the incision, the bigger the surgeon (in reputation). So that was a major paradigm shift, when you were able to do things effectively through smaller incisions. It was also a major paradigm shift in the way the medical community thought.

I imagine that shrunk a few egos?

Yes, a whole bunch. That’s why it was difficult to get the concept published. It was eventually published in Surgery, Gynaecology and Obstetrics and they published it in a very small section at the end of the journal called Surgeon at Work. Prior to the acceptance by SG&O, it was turned down by four major journals – Surgery, Archives of Surgery, JAMA and Annals of Surgery.

Do they regret it now?

I don’t think they even know about it.

What was the reaction to the paper?

It wasn’t immediate, but anybody who used the catheter recognized its importance right away. The academic community thought it was too dangerous and did not want other people to think it was an acceptable therapy. At that time, in the development of vascular surgery, you were not supposed to touch the inside of the vessel with anything. Essentially the catheter was scraping the inside the vessel; they thought if you did that the vessel would occlude. Contrary to perception, it did work.

Did it feel good to break the rules?

It felt good that it was working better than any other technology. And it’s still the most commonly used procedure to clear arteries.

If an invention is always good, do we always need proof of efficacy?

You do need proof of efficacy. The question is how much proof and how you get it. The problem is that it’s not needed with general surgeons so much, but certainly, internists need proof of efficacy. In the field of surgery, if you do something 100 times and 90% of the time it doesn’t work, it’s failed. If you use new technology and it works 90 out of 100 times, it’s an improvement. It doesn’t take Newtonian thought to realize that one is better than the other. It may not be to the level of evidence that Professor Greenhalgh wants, but the patients sure like it.

How many tests are needed?

There’s a thing called evidence-based medicine (EBM). The cornerstone of EBM is a comparative study – if you include randomization, it is the highest level of evidence. And everybody wants to write a good paper so their approach is to do a prospective blinded randomized study. It’s wrong because you should do what is in the best interest of the patient.

What are the alternatives?

You have to take advantage of your experience. And you don’t have to repeat a bad experience when you see a new technology is a much better. It’s almost intuitive. “I got this big clot out. I got it out very easily and quickly. I didn’t need a general anesthetic, only a tiny incision and local anesthetic was required and the survival rate was significantly improved.” It’s so obvious that you don’t have to endanger a patient with a randomized study.

Something that you are working on changing?

I am working on changing when to use and not use randomized controlled trials.

Do you have any other interests?

I have a winery. Both red and white grapes. Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Cabernet, Champagne and Merlot. The wines are on the market. The name is very original – Thomas Fogarty.

Family

I have four children. Three boys, one girl. The boys have all worked in the winery at some point in time. Right now two of them are professional race-car drivers. They’ve done open wheel and closed wheel, they’ve done the things that look like Indy Cars on an oval, and the closed wheel cars in the form of sports cars and the endurance races where 2/3 drivers will alternate and drive for 12 hours.

My daughter is a grand prix jumper – horses. She breeds and raises horses, she buys and sells them.

I have one granddaughter and another one on the way.`

Fact File:

Thomas J Fogarty, MD

Born: February 25, 1934, Cincinnati, Ohio

Family: Wife: Rosalee M Fogarty

Thomas James Jr, Heather Brennan, Patrick Erin, Jonathan David

Education

Undergraduate:

1952-1956: Xavier University, BS Biology, Cincinnati, Ohio

Medical School:

1956-1960: University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, M.D., Cincinnati, Ohio

Internship:

1960-1961: University of Oregon Medical School, Portland, Oregon

Residency:

1962-1965: University of Oregon Medical School, Portland, Oregon

1967-1968: Instructor in Surgery, University of Oregon Medical School, Portland, Oregon

1969-1970: Chief Resident and Instructor in Surgery, Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California

Fellowships:

1961-1962: Peripheral Vascular Disease, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio

1965-1967: Clinical Associate for National Heart Institute, Surgery Branch, Bethesda, Maryland

1968-1969: Advanced Research Fellow, Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, CA

Professional experience

1969-1970: Instructor of Surgery, Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California

1970-1971: Assistant Professor of Surgery, Full Time Faculty, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California.

1971-1973: Assistant Clinical Professor of Surgery, Clinical Faculty, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California.

1973-1978: Private Practice (Cardiovascular Surgery), Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California.

1973-1975: President, Medical Staff, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California.

1978-1993: Private Practice (Cardiovascular Surgery), Sequoia Hospital, Redwood City, California

1980-1993: Director, Cardiovascular Surgery, Sequoia Hospital, Redwood City, California.

1993-2001: Professor of Surgery , Full Time Faculty , Stanford University Medical Center.

2001-now: Clinical Professor of Surgery, Clinical Faculty, Stanford University Medical Center.

Memberships