The first results from the BEST-CLI randomised controlled trial (RCT) of 1,830 patients show that surgical bypass with adequate single-segment great saphenous vein (GSV) is a more effective revascularisation strategy for patients with chronic limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI) who are deemed to be suitable for either an open or endovascular approach. Researchers also found that both strategies can be accomplished safely and are effective for treatment for CLTI.

Further, the triallists urge that patients with CLTI who are candidates for limb salvage should undergo an evaluation of surgical risk and conduit availability. “Bypass surgery with adequate single-segment saphenous vein should be offered as a first-line treatment option for suitable candidates with CLTI as part of a fully informed shared decision-making. Level one evidence from BEST-CLI does not support an endovascular-first approach to all patients with CLTI. In patients without a suitable single-segment saphenous vein, both surgical and endovascular strategies are effective in treating patients with CLTI, so we believe that there is a complementary role for both revascularisation strategies in these patients,” they say, bringing the “quality of vein” back into the centre of discussion on revascularisation strategy.

The co-principal investigators—Alik Farber (Boston Medical Center, Boston, USA), Matthew Menard (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA), and Kenneth Rosenfield (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA)—note that this is the largest RCT comparing revascularisation treatment strategies in patients with CLTI and will provide important information regarding the management of these patients.

Today, Farber presented the much-anticipated clinical results, and Menard the quality-of-life analysis, from BEST-CLI at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions (5–7 November, Chicago, USA). The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

BEST-CLI (Best endovascular versus best surgical therapy for patients with CLTI) randomised patients with CLTI and infrainguinal peripheral arterial disease (PAD) to receive either infrainguinal bypass or endovascular intervention. The trial consisted of two parallel trials: Cohort 1 included patients with single-segment great saphenous vein; Cohort 2 included patients who lacked single-segment GSV and therefore alternative autogenous vein or prosthetic was used in those randomised to the open arm.

According to Farber, the best way to evaluate whether a patient has single-segment GSV—one he says needs to be at least 2.5mm in diameter, but ideally above 3mm, and must be free of thrombus—is by using duplex ultrasound. Speaking to Vascular News on this topic, Menard notes that while assessment of the vein is common practice for vascular surgeons, it is not for other specialties. In the wake of BEST-CLI, he suggests that evaluation of the GSV—a “very important” part of the assessment for treatment—should be included in the guidelines.

Farber tells Vascular News: “We are not claiming to bring down the 10 commandments here; all we are saying is that we are introducing some level one data into a space that has almost no Level one data.[…]. Here is another study that says the endovascular-first [approach] is a great thing for some people, but [it is] not for everybody. So, if a patient is a candidate for surgery and [..] has a good single-segment saphenous vein, there should be a conversation about surgery, for that individual.”

Key results

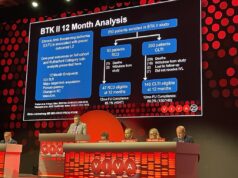

The investigators found that surgery was more effective than endovascular therapy in the Cohort 1 patients. At AHA, Farber revealed that there was a reduced rate of major adverse limb event (MALE) or all-cause death—the primary endpoint—in patients with good single-segment GSV who underwent open surgery, as well as fewer major reinterventions, at median follow-up of two point seven years. The maximum follow-up time in these patients was seven years.

Going into the details, Farber noted that Cohort 1 included 1,434 patients with single-segment GSV who were randomised 1:1 to either surgical or endovascular treatment. At median follow-up, the rate of MALE or all-cause death was 42.6% in the surgery arm compared to 57.4% in the endovascular arm (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59 to 0.79; p<0.001). In terms of secondary endpoints, he revealed that 10.4% of patients in the surgery arm underwent above-ankle amputation of the index limb versus 14.9% in the endovascular arm, in addition to rates of 9.2% vs. 23.5% for major reintervention on the index limb and 33% vs. 37.6% for all-cause death for patients in the open and endovascular arms, respectively.

In patients who did not have adequate saphenous vein, i.e. those in Cohort 2, there were no significant differences in the primary endpoint. Farber detailed that that this group included 396 patients who were randomised 1:1 to either surgical or endovascular treatment. The median follow-up was one point six years and maximum follow-up, five point one years. Farber reported that the rate of MALE or all-cause death in this cohort was 42.8% vs. 47.7% in the open and endovascular arms, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.06; p=0.12). The corresponding figures for the secondary endpoints were as follows: 14.9% vs. 14.1% for above-ankle amputation of the index limb; 14.4% vs. 25.6% for major reintervention on the index limb; and 26.3% vs. 24.1% for all-cause death.

Farber added that there were no differences in perioperative mortality or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and that mortality and MACE were similar between treatment strategies over the course of follow-up.

While the primary focus of the trial was clinical outcomes in the comparison of open surgery versus endovascular therapy, Menard tells Vascular News that the investigators planned two “very important” ancillary assessments: cost-effectiveness—which the team is yet to conduct—and quality of life. With regards to the latter, he noted that the team used a number of different metrics for this, including the vascular disease-specific VascuQoL, as well as the EQ-5D and the SF-12.

According to Menard, the baseline scores for quality of life speak to the impact of CLTI on patients’ everyday lives: “The quality of life for all patients at baseline on entry into the trial was extremely poor and low, and that is consistent with what is known about the devastating impact of CLTI on patients’ overall function, the mental status, their physician limitations, and their high degrees of pain.”

Menard reports that both revascularisation strategies resulted in “significant gains” across every metric studied, noting also that there was not any significant difference between the two treatment arms.

Making the case for the benefits of the endovascular approach, Rosenfield emphasises: “This is the first trial that really shows that when you compare ‘endo’ to surgery, certainly in the disadvantaged vein group, they both actually had durable outcomes. A lot of us had questions about how durable outcomes for the ‘endo’ approach would be. And it should be clear that it is an approach, because sometimes touch-ups are needed on both sides and those are not considered MALE events. You really had to have a major reintervention to reach an endpoint of MALE, or an amputation. But I think that this for the first time shows that, in a head-to-head trial, that both are durable and that, on the ‘endo’ side, once you achieve successful technical outcome, it is comparable even in the group that had reasonable vein in cohort one.”

BEST-CLI meets “astronomic” need for high-quality, practice-changing data

BEST-CLI meets “astronomic” need for high-quality, practice-changing data

At AHA, Farber noted that data from the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) from centres of excellence in North America revealed “tremendous” centre-specific variability in treatment strategy in the use of bypass versus endovascular for CLTI patients, which BEST-CLI national trial manager Michael Strong tells Vascular News attributes to the lack of evidence-backed guidelines in the space.

Speaking to this newspaper, the investigators express their confidence that the results of BEST-CLI will change practice and impact the Global Vascular Guidelines published in 2019. Menard believes there is “no question” that guidelines will change, partly because the current guidelines are “riddled with gaps”. He notes that anywhere from 10–15% of current guidelines are based on level one data—a “miserably low” figure in his opinion. “The need for quality data that the BEST-CLI represents is astronomic,” he says.

Rosenfield remarks that the trial will “definitely change practice” as it provides the clear message that “surgery is not dead, in fact it is very much alive and well for the appropriately selected patients”. He stated that the data “should be described to patients—simple as that,” and that patients “should have the option of deciding, but they should be knowledgeable that they will do better with surgery [in selected cases], and that is an appropriate response to [these results].”

Farber concurs, noting that there is now level one evidence to support the role of bypass in certain patients. “It supports a body of literature that is not as strong, and so I think [guidelines] will change,” he comments.

“I think it is nice for us to have all these arrows in our quiver to treat CLTI patients, and that is what this is; it is about saying this arrow does work and it should be used in some situations,” Farber summarises. “That is a great thing to add because, before BEST-CLI, the data were not as strong.”

“The first step”

While the investigators agree that BEST-CLI will be practice changing, they acknowledge that it represents “the first step” in a long trajectory of future investigations and discussions in CLTI research.

At AHA, Farber noted some limitations of the trial, including selection and operator bias in enrolment and intervention, the fact that equipoise and eligibility were determined locally and were variable, and that anatomic complexity is yet to be evaluated. In addition, cohort 2 was likely underpowered, anatomic complexity yet to be evaluated, percentage of female patients lower than targeted, and use of paclitaxel balloons or stents affected by the Katsanos meta-analysis during enrolment, they elaborate.

“We need to dig deeper,” Rosenfield says. He describes the trial as a “game-changer in many respects,” but stresses that “this field is still a moving target” and so BEST-CLI must be seen as “the first foray into developing very solid level one evidence”. Specifically, he notes that techniques will “continue to improve and get better”. Looking ahead, Rosenfield believes that those who treat CLTI will “learn a lot more over the course of the next couple of years as we peel back the layers of the onion”.

According to Menard, the trial stimulates two topics that will take centre stage in the “great discussions that are going to be had” in the coming months. “We are all trying to figure out exactly how we are going to interpret the results for our own practices, and in order to do that, you really need to understand the patients enrolled into the trial, and that is a big focus of the future work—defining what their anatomy was […] and a bit more about overall demographics. You can have selection bias, but you cannot imply or in any way get around the fact that at that institution they were deemed appropriate for both [open and endovascular strategies],” he tells Vascular News.

Farber stresses that further investigation might also elucidate how an operator decides between adopting an open or endovascular approach in certain patients. “We all know that if it is an easy ‘endo’, then of course the patient should have an ‘endo’, there is no equipoise, and then on the other extreme there are cases where everything is blocked from the groin to the foot and somebody might say of course surgery is the way to go, and then there is everything in between,” he says. What remains, according to Farber, is for the investigators and others in the field to “dig deep” into these data to answer the question of how to define appropriateness for a certain treatment.

For now, Rosenfield notes that the investigators are “really excited” about analysing the “treasure trove” of data that BEST-CLI provides and seeing what they can learn. Looking beyond this, Menard expresses the team’s hope that “many more trials will come along and build on what the trial has laid as a foundation”.