The first European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guideline on treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), published in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery in 2011,1 has had a major impact on clinical practice and research. However, due to the rapid developments of the field it has become outdated. In 2015, the process to update the ESVS AAA guideline was initiated. A writing committee consisting of 16 vascular surgeons from all over Europe worked out a comprehensive document, comprising 97 pages, including 790 references with a total of 125 recommendations. For the first time, ESVS Guidelines were written in collaboration with patient representatives. The document has undergone three review rounds by 13 external reviewers from Europe, the USA, Asia and Australia, as well as by the 10 members of the ESVS guideline committee. The resulting “European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysm” were presented at the ESVS annual general meeting (25–28 September, Valencia, Spain), published online in November 2018, and will appear in the January 2019 issue of the printed journal.2

Here we summarise some news of importance to vascular specialists as well as policy makers, and briefly discuss notable differences between the ESVS guidelines and other contemporary guidelines; the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) AAA guidelines published in 2017,3 and the draft of the upcoming National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) aortic guideline targeting England and Wales.4

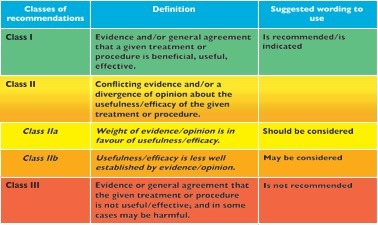

Figure. The recommendations in the ESVS guidelines are based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) grading system.

Figure. The recommendations in the ESVS guidelines are based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) grading system.

Service standard

The management of AAA has changed profoundly with the introduction of endovascular treatment. Studies have convincingly shown the benefit of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) in both elective and emergency AAA repair in patients with suitable anatomy. At the same time, it is evident that some patients are not suitable for standard EVAR, or more complex endovascular treatment options, but should be offered open surgery. Consequently, one technique cannot entirely replace the other. Compromising the anatomical requirements for standard EVAR, using complex and partially experimental endovascular techniques to avoid established open surgical solution at all cost, or solely offering major open surgery when there are proven minimally invasive techniques, just because it is outside office hours, is not in accordance with good clinical practice. Thus, today it is not acceptable to perform abdominal aortic interventions without the ability to offer both endovascular and open surgical technologies 24/7 (Recommendation 2; Class I, Level B).

The firm evidence of a volume-outcome relationship of surgery in general, and AAA repair in particular, makes it necessary and justifiable to make a recommendation on minimal surgical volume. No clear threshold was possible to identify in the literature, however. Various cut-off levels have been suggested, and other aspects have to be taken into account, such as population density and geographical distances. Based on the literature the ESVS guideline writing committee (ESVS-WC) concluded that there is enough evidence for a rather weak recommendation on a desired minimum hospital volume of at least 30 cases annually (Recommendation 3; Class IIa, Level C) while a stronger recommendation can be issued on a minimum yearly case load of at least 20 repairs to perform aortic surgery at all (Recommendation 4; Class III, Level B). This is essentially in line with what the SVS recommends (an annual minimum volume of 10 cases for each open surgical repair and EVAR), and justifies a continued centralisation to medium and high volume centres. The NICE guidelines draft does not address this topic.

There are limited data concerning a reasonable waiting time for treatment once the threshold for repair has been reached. Although there is no strong evidence to support exact timings, it is reasonable to adopt a similar approach as for other life threatening diseases, such as cancer. Based on the rupture risk, as well as the psychological consequences, a suggested upper limit for the total pathway from referral to treatment is eight weeks, once the intervention threshold is reached. This applies, however, only to standard AAA cases, whereas in more complex aneurysms or comorbid patients a longer planning and/or work-up time is justified. Correspondingly, a shorter timeframe should be pursued for larger AAAs (Recommendation 5; Class I, Level C). Those of us who fail to meet this requirement should promptly develop routines for fast-track preoperative imaging and work-up. Modern cancer care often has well-structured treatment pathways with clearly defined deadlines, and may serve as a role model.

Elective AAA repair

Due to the rapid technological and medical development, the existing randomised controlled trials comparing open surgical repair (OSR) and EVAR are partly outdated and thereby not entirely relevant for today’s situation. The evidence from RCTs also has the limitation that they mainly apply to patients <80 years of age, whereas today the greatest increases in AAA repair is among those >80 years. This group has also seen the most pronounced improvement in outcome after AAA repair, likely related to the preferential use of EVAR for treatment among octogenarians. It is therefore necessary to also include more recent case series and registry studies in the overall evaluation of the evidence base. Thus, despite data from multiple RCTs and meta-analysis, representing the highest level of evidence, we rate the existing level of evidence as mediocre (Level B). Overall, evidence suggests a significant short-term survival benefit of EVAR over OSR, with similar long-term outcome up till 10–15 years of follow-up. Thus, in patients with suitable anatomy and reasonable life expectancy, EVAR should be considered as the preferred treatment modality (Recommendation 60; Class IIb, Level B). Yet, there are indications that increased rate of complications may occur after eight to 10 years with earlier generation EVAR devices and an uncertain durability of current devices, particularly the low profile devices. Thus, although EVAR should be considered the preferred treatment modality in most patients, it is reasonable to suggest an OSR first strategy in younger, fit patients with long life expectancy, i.e. >10–15 years (Recommendation 61; Class IIa, Level B).

These recommendations, which more clearly than before favour EVAR over OSR in most scenarios, differ significantly from the NICE guideline draft, where EVAR is not recommended at all in the elective setting. It is obvious that the ESVS guidelines writing committee has interpreted the literature completely differently, taking into account the fact that the RCTs comparing open surgical repair and EVAR are outdated, while the NICE committee has not done the same assessment. The SVS recommend the use of a perioperative mortality risk scoring system to guide the choice of surgical technique, emphasising the importance of patient involvement.

Ruptured AAA repair

When pooled together, the one-year results of the three recent RCTs (IMPROVE, AJAX, ECAR) suggest that there is a consistent but non-significant trend for lower mortality post EVAR. The IMPROVE trial found faster discharge with better quality of life post EVAR, which therefore was cost effective. The recently published three-year results of the IMPROVE trial suggest that, compared with OSR, an endovascular strategy for suspected ruptured AAA was associated with a survival advantage, a gain in quality of life adjusted years, similar levels of reintervention, reduced costs, and this strategy was cost effective. These findings, together with observational studies and registry data, support a strong recommendation of an EVAR first strategy for ruptured AAA repair (Recommendation 74; Class I, Level B). This recommendation—a major change from the previous ESVS guidelines—is in agreement with both the SVS guidelines and the NICE guideline draft.

New devices

In recent years, manufacturers have developed new stent grafts and delivery systems with lower profiles to allow an endovascular approach even in patients with small access vessels. Although there are some series reporting favourable midterm outcomes for last-generation low-profile stent grafts compared to standard profile stent grafts, more experience and longer-term outcome data, especially about the durability, are needed to confirm those findings. Therefore, when upgrades of existing platforms are used in clinical practice, the need for long-term follow-up should be recognised, and evaluation in prospective registries with complete follow-up is strongly recommended (Recommendation 57; Class I, Level C).

Novel new techniques and treatment concepts, such as endovascular aneurysm sealing with polymer-filled endobags (EVAS) has only been commercially available for a limited time, and their effectiveness and durability are still under investigation. We issue a strong negative recommendation of its use in clinical practice outside studies approved by research ethics committees and with informed consent from the patients, until adequately evaluated (Recommendation 58; Class III, Level C). This approach is supported by recent alarming reports of higher-than-expected rates of leaks around the implant, device movement, and aneurysm enlargement after EVAS.

Neither the SVS guidelines, nor the NICE guideline draft, address this topic, which we consider of great importance given the continued rapid industry driven technical development. CE marking (or approval) is a certification mark for products sold within the European Economic Area (EEA), i.e. European Union (EU) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Unlike the rigorous evaluation of efficiency and safety required for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the USA, CE marking has nothing to do with efficiency or safety. Thus, the role for several new innovative CE marked technologies on the market is still unclear and further data are needed before these can be recommended to be used in routine clinical practice.

Follow-up after EVAR

Due to the risk of graft-related complications and rupture after EVAR, regular imaging follow-up has been regarded as mandatory. The true value of prophylactic regular follow-up imaging after EVAR is uncertain, however. Routine surveillance seldom identifies significant findings requiring reintervention, and most patients who require re-intervention after EVAR present with symptoms. Compliance with annual prophylactic imaging guidelines is suboptimal and lack of adherence to follow-up does not seem to affect long-term mortality or post-implantation rupture rate. Thus, annual imaging after EVAR for all patients is neither evidence-based nor feasible.

An early postoperative clinical and imaging follow-up after EVAR is required to assess the success of the performed intervention (Recommendation 91; Class I, Level B). Recent data suggest that patients considered at low risk for endovascular aortic repair failure after their first postoperative computer tomography angiography, i.e. no endoleak, anatomy within IFU, adequate overlap and seal of ≥10mm proximal and distal stent graft apposition to arterial wall, may be considered to be stratified to less frequent follow-ups, with delayed imaging up till 5 years after repair (Recommendation 92; Class IIb, Level C). Patients who do not meet these requirements should be assessed for the need for reintervention or continued frequent monitoring.

In contrast to the above approach with risk stratification, the SVS guidelines recommend continued annual imaging follow-up for all patients post EVAR. While the NICE guideline draft does not indicate a specific frequency for follow-up, it supports that it should be guided by the individual patients estimated risk of graft related complications.

Juxtarenal AAA

Given the rarity and complexity of JRAAA treatment centralisation to specialised high volume centers that can offer both open and complex endovascular repair seems justified and is recommended (Recommendation 94; Class I, Level C).

Complex endovascular techniques have emerged as promising alternatives, or complement, to OSR for the treatment of JRAAA. However, reliable comparative and health-economic studies are still missing. Consequently, decision making is complex and should be tailored to each individual patient and local health economies. Stratification of cases by anatomy and surgical risk may be useful in patients with JRAAA (Recommendation 95; Class IIa, Level C). OSR with an anastomosis below the renal arteries and short renal clamping time may be a preferable and durable option for fit patients with a short aortic neck. With more complex anatomy or high surgical risk due to comorbidities an endovascular solution may be preferable.

Despite limited data, it is the ESVS-WC assessment that fenestrated technology has a small advantage over parallel graft technique when it comes to proven feasibility and durability, as there are more multicenter reports and longer follow-up data available, and thus it should be the preferable endovascular technique for elective JRAAA repair (Recommendation 96; Class IIa, Level C).

Parallel graft techniques may, however, be considered as an alternative technique in the emergency setting or as a bailout (Recommendation 97; Class IIb, Level C), but one should then aim for a proximal landing zone of at least 15 mm, ensure a proper stent graft-oversizing of 30%, and use a maximum of two chimneys.

As for standard AAA repair, novel new techniques and treatment principles, such as EVAS, Endostaples and in-situ fenestration are not recommended in clinical practice for JRAAA repair but should be limited to studies approved by research ethics committees and with informed consent from the patients (Recommendation 98; Class III, Level C).

Data is even more scarce for ruptured JRAAA, but the risk aversion is lower in such an immediate life threatening and complex situation. Therefore, in patients with ruptured JRAAA open repair or complex endovascular repair (with physician modified fenestrated stent grafts, off-the-shelf branched stent graft, or parallel graft) may be considered based on patient status, anatomy, local routines, team experience and patient preference (Recommendation 99; Class IIb, Level C).

JRAAA is not covered by the SVS guidelines, while the NICE guideline draft clearly recommend against any use of complex EVAR outside randomised clinical trials. Again, a big difference with potential huge clinical impact compared with the recommendations made in ESVS guidelines, and our views of the current knowledge are remarkably different. With today’s rather extensive experience of complex EVAR (especially fEVAR), showing generally good results, and the ability to offer treatment to many patients less suitable for major open surgery; it is difficult to motivate a strong preference for OSR over complex EVAR for JRAAA. Instead, we favour a more pragmatic approach, with OSR and EVAR complementing each other.

Conclusion

We encourage everyone to carefully read the new ESVS aortic guidelines in its entirety. It is an extensive document but offers many more recommendations of clinical importance (including recommendations on medical management, screening, iliac aneurysms, mycotic and inflammatory aneurysms, concomitant malignant disease, etc.) and a comprehensive supporting text that summarises the literature and motivates our positions. We hope you will find the document relevant and useful for your practice.

Anders Wanhainen is chair and corresponding author of the ESVS AAA Guideline Writing Committee. He is also professor of Surgery, Department of Surgical Sciences at Uppsala University in Uppsala, Sweden.

Gert J. de Borst is chair of the ESVS Guidelines Committee and professor of Vascular Surgery, Department of Vascular Surgery at University Medical Center Utrecht in Utrecht, the Netherlands.

References

- Moll FL, et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms clinical practice guidelines of the European society for vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41:S1e58.

- Wanhainen A, et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms, European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.09.020

- Chaikof EL, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jan;67(1):2-7

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-cgwave0769/documents