Distal embolic protection using a filter has been associated with improved transfemoral carotid artery stenting (tfCAS) outcomes in terms of in-hospital stroke and death risks—underpinning current Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) guidelines recommending routine use of distal embolic protection during carotid stenting, and supporting the notion that, “if a filter cannot be placed safely, an alternative approach to carotid revascularisation should be considered”.

Sophie Wang, Patric Liang (both Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA) and colleagues deliver this message in a recent Journal of Vascular Surgery (JVS) publication detailing a retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort analysis of tfCAS patients in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) across a 16-year period.

“Transfemoral carotid stenting without use of embolic protection is associated with a significant increase in in-hospital stroke/death compared with tfCAS performed with distal filter placement,” the authors write. “Failed attempted filter placement is associated with worse outcomes after tfCAS, but stroke/death rates are no different than those seen in patients in whom a filter was never attempted.

“These findings support the current guideline recommendation for routine use of distal embolic filters during tfCAS. However, the proportion of non-protected tfCAS performed annually is increasing, and there is significant variability in routine filter usage across physicians and centres in the VQI.”

In an effort to assess in-hospital outcomes in patients undergoing tfCAS with and without embolic protection using a distal filter, Wang, Liang and colleagues identified all patients undergoing this procedure in the VQI from March 2005 to December 2021—excluding those who received proximal embolic balloon protection. As well as creating propensity score-matched cohorts of patients who underwent tfCAS with and without attempted filter placement, they performed subgroup analyses of patients with ‘failed’ versus ‘successful’ filter placement, and ‘failed’ versus ‘no attempt’ at filter placement.

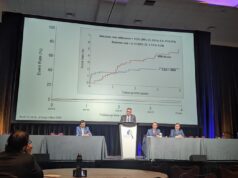

In-hospital outcomes were assessed using log binomial regression, adjusted for protamine use, the authors detail. Their outcomes of interest were composite stroke/death, stroke, death, myocardial infarction (MI), transient ischaemic attack (TIA), and hyperperfusion syndrome.

Among 29,853 patients who underwent tfCAS, 28,213 (95%) had a filter attempted for distal embolic protection and 1,640 (5%) did not. After propensity-score matching, 6,859 patients were identified.

In comparison to cases in which a filter placement was attempted, no attempted filter was associated with a significantly higher risk of in-hospital stroke/death (6.4% vs 3.8%)—constituting a more than two-fold increase in stroke/death risk, as per the analysis’ key outcome of interest. Similar trends were observed regarding stroke (3.7% vs 2.5%) and mortality (3.5% vs 1.7%) too.

In a secondary analysis of patients who underwent a failed attempt at filter placement—versus successful filter placement—failure was associated with worse outcomes (stroke/death: 5.8% vs 2.7%; stroke: 5.3% vs 1.8%, respectively). However, Wang, Liang and colleagues observed no statistical difference in outcomes in patients with failed versus no attempted filter placement (stroke/death: 5.4% vs 6.2%; stroke: 4.7% vs 3.7%; death: 0.9% vs 3.4%) after adjusted analysis.

“Distal embolic protection confers a benefit in stroke/death rates following tfCAS compared to unprotected stenting,” the authors conclude, putting forward their ‘take-home message’ in JVS. “Failure to place a filter should prompt exploration of alternative carotid revascularisation approaches.”