A new study from Keck Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC; Los Angeles, USA) has uncovered “significant racial disparities” in the diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of peripheral artery disease (PAD) among Black and white patients in the USA.

“We discovered that Black patients are nearly 50% less likely to receive vascular interventions to potentially restore the blood flow than white patients, and consequently are at a disproportionately higher risk of a stroke, heart attack or amputation,” said David Armstrong (Keck Medicine, Los Angeles, USA), an author of the study. “Additionally, Black patients tend to have more advanced PAD and are sicker at the time of diagnosis, indicating they may not be getting as timely medical attention as their white counterparts.”

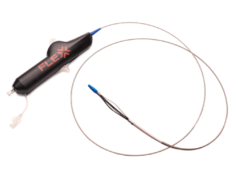

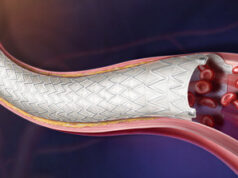

Once detected—generally through a blood test—PAD is typically treated with medication to reduce the plaque in the arteries, and through suggested lifestyle changes, such as increased exercise and a healthy diet. If these measures do not work, physicians often recommend a revascularisation procedure, which can reduce the risk of a heart attack, stroke or amputation of the affected limb.

The recent Keck Medicine study discovered that Black patients are more likely to only receive medication and lifestyle change recommendations, while white patients also receive revascularisation.

“Our findings suggest Black patients are missing out on potentially limb- and life-saving treatments,” Armstrong added. “And, because Black patients tend to be sicker at the time of diagnosis than white patients, they may actually be in more need of a revascularisation than other patients.”

Armstrong and his colleagues used a large national database to compare rates of diagnostic testing, treatment patterns and outcomes after diagnosis of PAD among commercially insured US patients from 2016 to 2021. Having identified some 455,000 white patients and 96,000 Black patients, they compared demographics, markers of disease severity and healthcare costs, as well as patterns of medical management and rates of amputation and cardiovascular events, among the two patient groups to reach their conclusions.

While the study did not analyse why disparities in the detection, treatment and outcomes of PAD between Black and white patients exist, one factor may be that Black patients are already at a higher risk of developing PAD, according to Armstrong. He also hypothesised that the inequalities may be due to broader systematic issues—such as unconscious bias or barriers to healthcare access for certain populations.

“We hope this study will encourage physicians to take these differences into account when diagnosing and treating PAD to ensure that vascular interventions are being equally provided to all patients,” he said. “We also urge health professionals to offer more routine screenings for PAD in Black patients.”

Additionally, Armstrong advised patients to proactively seek medical advice and testing if they have any symptoms related to PAD—leg cramping, pain, numbness, weakness or discoloration—and advocate to be considered for all treatment options after diagnosis.